Volume 6, Issue 3 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(3): 161-167 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.480

History

Received: 2025/06/3 | Accepted: 2025/07/8 | Published: 2025/07/12

Received: 2025/06/3 | Accepted: 2025/07/8 | Published: 2025/07/12

How to cite this article

Ameri Felihi N, Bavi S, Farashbandi A. Effect of Resilience and Self-Compassion Training on Emotion Regulation and Frustration Tolerance in Students with Clinical Aggression Symptoms. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (3) :161-167

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-430-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-430-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Campus (Ahv.C.), Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (366 Views)

Introduction

Aggression among adolescents, especially female students, has emerged as a significant global concern, exhibiting a complex interplay with psychological and social health. This behavior, which can manifest as physical, verbal, or relational hostility, often indicates underlying emotional dysregulation and coping deficits [1]. Studies have consistently linked aggressive behavior in youth to a range of adverse outcomes, including academic difficulties, strained peer relationships, and an increased risk of future mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety [2, 3]. In the context of the school environment, aggression disrupts the learning process, compromises school safety, and places a heavy burden on both the students involved and the educational system as a whole [4]. Addressing these behaviors is not merely a matter of discipline but a critical component of promoting well-being and fostering a supportive atmosphere for all students [5]. Therefore, understanding the psychological underpinnings of aggression and developing effective, targeted interventions is a priority for both researchers and practitioners.

Emotion regulation is a crucial skill involving the ability to influence which emotions one has, when one experiences them, and how one expresses them [6]. It is a complex process that includes both conscious and unconscious strategies to manage emotional states. Deficits in emotion regulation are a core component of many psychological disorders, and their link to aggressive behavior is well-documented [7]. Individuals who struggle to regulate their emotions are more likely to react impulsively and with hostility when confronted with challenging situations, as they lack the cognitive and behavioral tools to process their feelings in a constructive manner [8]. Research has shown that teaching adolescents effective emotion regulation strategies can reduce their aggressive tendencies and improve their overall psychological well-being [9].

Frustration tolerance, a closely related construct, refers to an individual’s capacity to cope with situations where goals are blocked or desires are unfulfilled without resorting to extreme emotional or behavioral outbursts [10]. Low frustration tolerance is a hallmark of many aggressive behaviors. When faced with obstacles, individuals with poor frustration tolerance may resort to anger, hostility, and destructive actions rather than employing adaptive problem-solving skills [11]. This can lead to a vicious cycle where a person’s inability to cope with setbacks results in more frequent and intense negative outcomes, further reinforcing their aggressive patterns [12]. Interventions aimed at improving frustration tolerance equip individuals with the resilience and self-control necessary to navigate the inevitable challenges of life without resorting to aggression [13].

Resilience training is a psychoeducational intervention designed to enhance an individual’s capacity to “bounce back” from adversity and stress [14]. It focuses on building internal resources such as problem-solving skills, a positive self-concept, and social support networks. Studies on resilience training have shown its effectiveness in various populations, including college students and workers, leading to reduced stress, improved coping mechanisms, and decreased symptomatology of depression and anxiety [15, 16]. When applied to aggressive adolescents, resilience training can provide a framework for developing adaptive coping strategies, enabling them to respond to challenging situations with greater emotional stability and less impulsivity [17]. By fostering a more resilient mindset, students can learn to view setbacks not as insurmountable obstacles but as opportunities for growth.

Self-compassion training, rooted in compassion-focused therapy, is a distinct yet complementary approach that involves treating oneself with kindness, understanding, and non-judgment, especially during times of failure or inadequacy [18]. It consists of three main components: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification [19]. Research has demonstrated that self-compassion is a powerful antidote to self-criticism, shame, and other negative self-evaluative emotions that often underlie externalizing behaviors like aggression [20]. A compassionate self-view can help individuals accept their flaws and failures, reducing the need to externalize their frustration through aggressive acts [21]. By cultivating self-compassion, individuals can develop a more gentle and accepting relationship with themselves, which, in turn, reduces their emotional reactivity and enhances their ability to cope with difficult feelings.

Despite the established links between aggression and deficits in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, as well as the potential of resilience and self-compassion as therapeutic interventions, there remains a need for comparative research in this area. While previous studies have examined these variables in isolation [14, 20], there is a gap in the literature regarding a direct comparison of the effectiveness of resilience training versus self-compassion training, specifically in the context of addressing aggression in female adolescents. The unique psychological and social pressures faced by this population necessitate targeted interventions that are empirically validated. This study aimed to fill this gap by providing a direct comparison of the two interventions. The primary objective of this research was to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of resilience training and self-compassion training on emotion regulation and frustration tolerance in female middle school students with clinical symptoms of aggression.

Materials and Methods

Design and Participants

This clinical trial, conducted in 2024, employed a pre-test, post-test, and a one-month follow-up design. The statistical population included all female middle school students, aged 13 to 15, with clinical symptoms of aggression in the city of Ahvaz. Using a random cluster sampling method, two educational districts were first selected at random from the city’s districts. From each of these two districts, two schools were randomly chosen, and from each school, two classes were randomly selected. After initial screening, a total of 45 students with clinical symptoms of aggression were identified. These participants were then randomly assigned to one of three groups: a resilience training group (n=15), a self-compassion training group (n=15), and a control group (n=15) that received no intervention.

Inclusion criteria included being a female student aged 13-15, exhibiting clinical symptoms of aggression based on the screening tool, and providing informed written consent from both the student and their parents. Exclusion criteria included missing more than two intervention sessions or having a history of receiving psychological treatment for aggression or related issues. All ethical considerations were carefully observed, including ensuring the confidentiality of all data and providing access to psychological support for all participants after the study was concluded.

Procedure

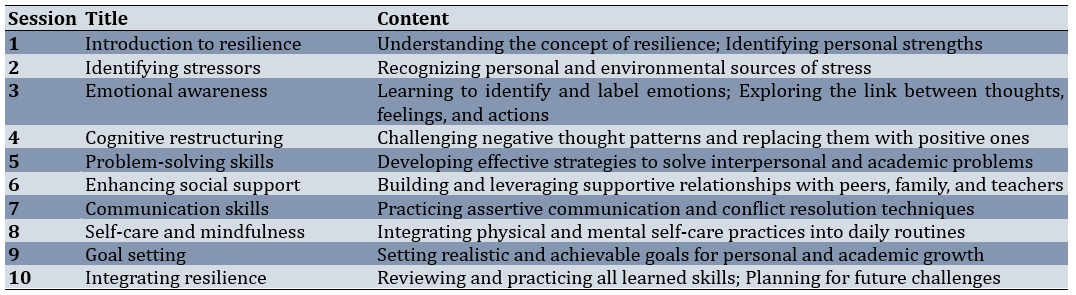

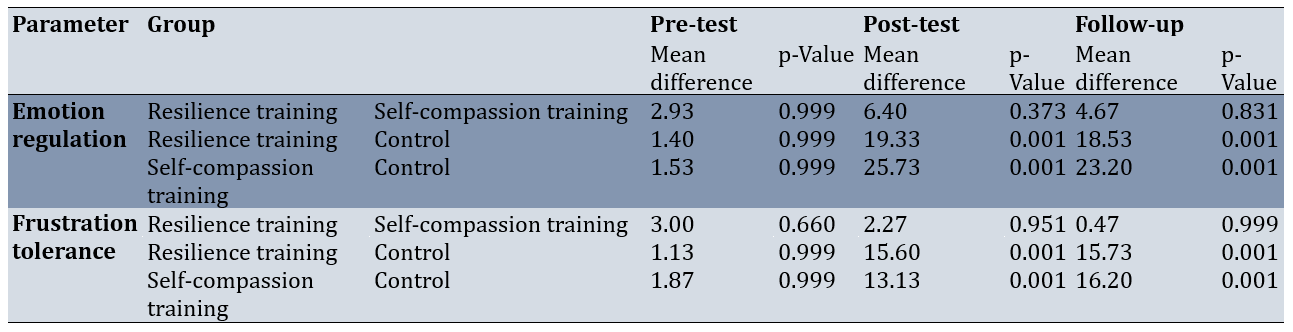

Following the random assignment of participants, a pre-test was administered to all three groups. The experimental groups then participated in their respective interventions. Resilience training was conducted over 10 weekly sessions of 75 minutes each (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the resilience training sessions

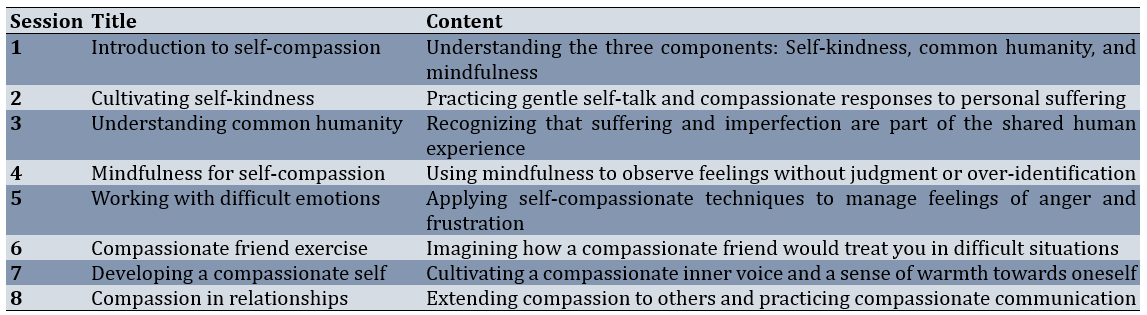

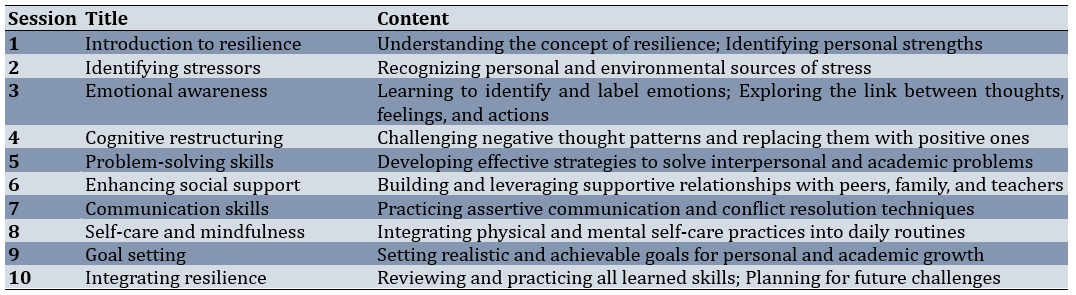

The compassion-focused therapy was implemented in 8 weekly sessions of 90 minutes (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of the self-compassion training sessions

The control group received no treatment during this period. After the interventions were completed, a post-test was administered to all three groups, followed by a one-month follow-up assessment to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the interventions.

Instrument

Affective Control Scale (ACS): Emotion regulation was measured using the 42-item ACS developed by Williams et al. [22]. This instrument consists of four components: anger, depressed mood, anxiety, and positive affect, and it is rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Higher total scores indicate better emotional control. The questionnaire has demonstrated strong validity and reliability; in a previous Persian-language study, its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.76 [23], and in the present study, the value was found to be 0.79.

Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS): Frustration tolerance was assessed using the FDS developed by Harrington in 2005. This instrument contains 35 items across four components, which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. It measures an individual’s ability to cope with obstacles and setbacks on the path to achieving their goals. Higher scores on this questionnaire indicate a greater capacity for frustration tolerance [24]. The reliability of this questionnaire in a previous Persian study was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 [25], and in the current study, it was 0.87.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27 software. The primary analytical method was repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was used to compare the changes in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores across the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases for all three groups. Prior to analysis, data were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming that emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores approximated a normal distribution. Homogeneity of variances was verified via Levene’s test. These findings supported the use of repeated measures ANOVA for subsequent analyses.

Findings

The study included 45 female middle school students aged 13 to 15 years. The mean age across groups was approximately 14 years (14.1±0.7), with no significant differences in age distribution, ensuring comparability among the groups.

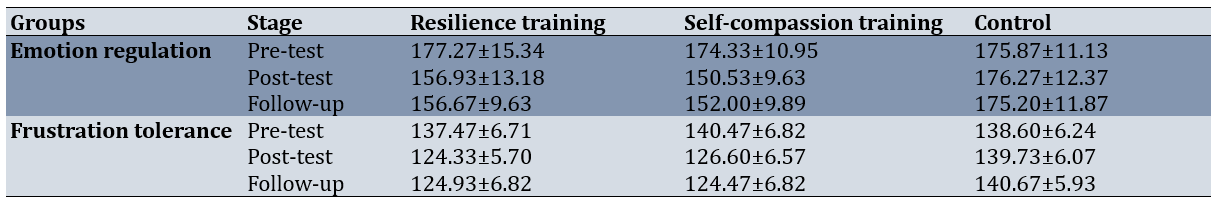

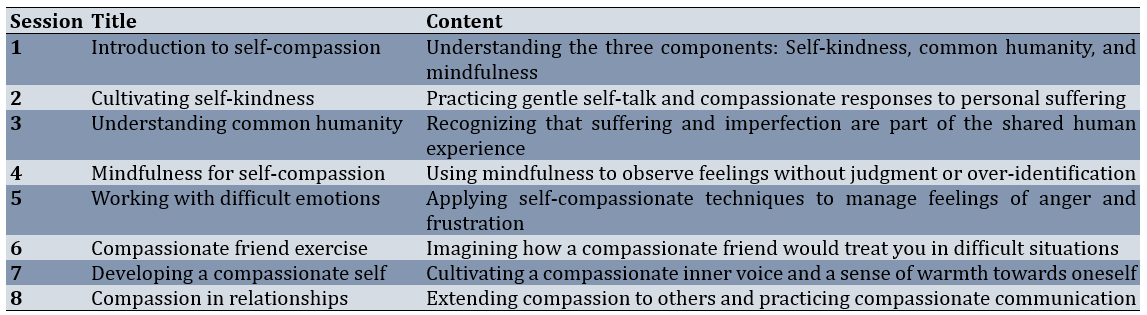

At the pre-test, the groups showed comparable scores for emotion regulation and frustration tolerance. Post-intervention, both experimental groups demonstrated significant improvements in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, which were sustained at follow-up, while the control group showed minimal change (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores across study phases

Significant main effects of time were observed for both emotion regulation and frustration tolerance (p<0.001). Significant time×group interactions were also found (p<0.001), indicating differential changes across groups over time. Group main effects were significant (p<0.001), suggesting variations in intervention efficacy (Table 4).

Table 4. Repeated measures ANOVA results for emotion regulation and frustration tolerance (p-Value=0.001)

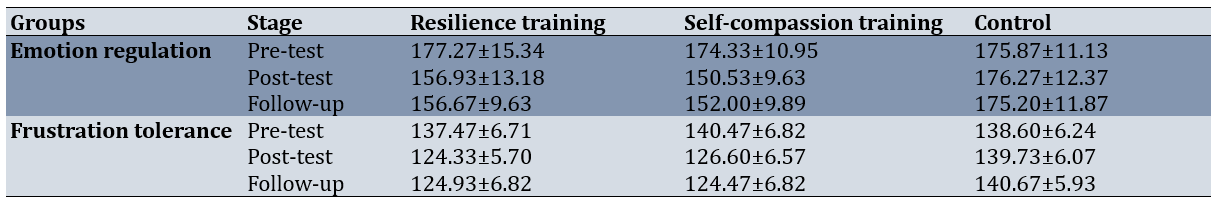

For emotion regulation, significant improvements from pre-test to post-test and follow-up were observed in both the resilience (p<0.001) and self-compassion groups (p<0.001), with no significant change in the control group. Similarly, frustration tolerance improved significantly in both experimental groups (p<0.001), but not in the control group (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons of emotion regulation and frustration tolerance across study phases

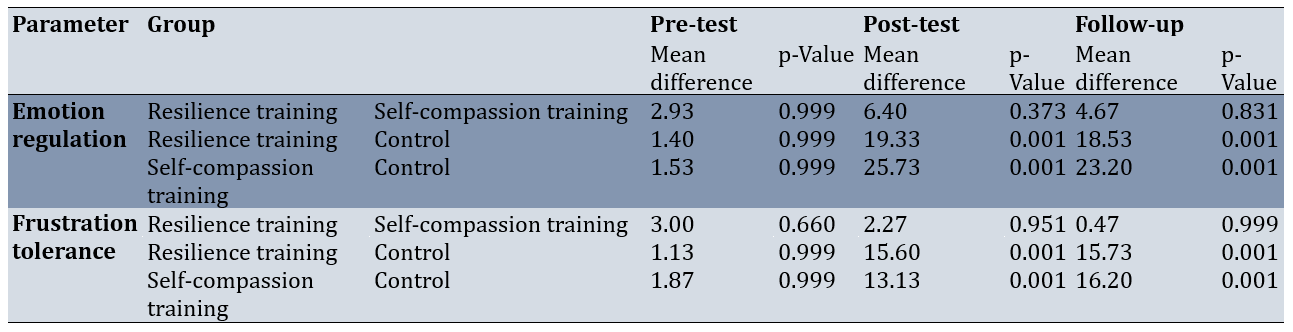

No significant differences were found between the resilience and self-compassion groups at any phase, indicating comparable efficacy (Table 6).

Table 6. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons of group differences in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance

Discussion

This study investigated the comparative effectiveness of resilience and self-compassion training on emotion regulation and frustration tolerance among female middle school students with clinical symptoms of aggression. Both interventions significantly enhanced emotion regulation and frustration tolerance compared to the control group, with effects sustained at the one-month follow-up. Notably, no significant differences were observed between the resilience and self-compassion groups, suggesting comparable efficacy. These findings align with and extend prior research, offering valuable insights into psychological interventions for adolescent aggression.

The effectiveness of resilience training in improving emotion regulation and frustration tolerance is consistent with existing literature. Previous studies have shown that resilience training enhances coping strategies, reduces stress, and mitigates symptoms of anxiety and depression in various populations [15, 16, 26]. For instance, Steinhardt and Dolbier [26] found that resilience interventions improve adaptive coping, which aligns with our observation of enhanced emotional control and frustration tolerance. This effect may be attributed to the intervention’s focus on cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, and social support, which equip students to manage stressors without resorting to impulsive or aggressive behaviors [27]. By fostering a mindset that views challenges as opportunities for growth, resilience training likely enhances adolescents’ ability to regulate emotions and tolerate frustration, thereby reducing aggressive tendencies [14].

Similarly, self-compassion training yielded significant improvements in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, corroborating prior research [20, 28]. Self-compassion, which encompasses self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, provides a framework for adolescents to process negative emotions without self-criticism or over-identification [19]. Abdollahi et al. [28] demonstrated that self-compassion moderates the relationship between stress and aggression, a finding supported by our results, in which participants exhibited reduced emotional reactivity and improved coping with setbacks. This may stem from self-compassion’s ability to create a non-judgmental internal space, allowing students to accept their emotional experiences and respond adaptively [21]. Studies by Wang et al. [29] and Guan et al. [30] further suggest that self-compassion mitigates externalizing behaviors by reducing perceived stress and fostering self-acceptance, which is particularly relevant for adolescents navigating social and identity-related challenges.

The absence of significant differences between the two interventions is a critical finding, suggesting that resilience and self-compassion training may target overlapping psychological mechanisms. Both approaches emphasize emotional awareness and adaptive coping, albeit through different lenses: resilience training focuses on building internal and external resources, while self-compassion promotes self-kindness and mindfulness [18]. For example, the mindfulness component of self-compassion training parallels the emotional awareness fostered in resilience training, potentially explaining their comparable outcomes [17, 19]. This convergence suggests that the interventions share core processes, such as enhancing self-regulation and reducing emotional reactivity, which are pivotal in addressing aggression [7, 9]. The flexibility to choose either intervention based on individual or contextual needs is a practical implication for clinicians and educators.

These findings have significant implications for school-based mental health programs. Given the detrimental impact of aggression on academic performance, peer relationships, and school climate [4, 5], implementing resilience or self-compassion training could proactively address these issues. Schools could integrate these interventions into counseling programs or curricula, tailoring delivery to suit diverse student populations. The sustained effects at follow-up underscore the potential for long-term benefits, supporting the adoption of such programs to foster psychological well-being and reduce aggressive behaviors.

This study underscores the efficacy of resilience and self-compassion training in enhancing emotion regulation and frustration tolerance among female students with aggressive tendencies. The comparable effectiveness of these interventions highlights their potential as interchangeable tools in clinical and educational settings. By addressing the psychological underpinnings of aggression, these interventions offer promising avenues for promoting mental health and fostering adaptive coping in adolescents.

The results suggest that both approaches can serve as valuable and interchangeable psychological interventions for mitigating aggression and promoting mental well-being in the adolescent population. The similar outcomes indicate that their underlying mechanisms, which likely include enhancing emotional awareness and acceptance, are potent drivers of positive and lasting change in these key psychological skills.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations. The sample was restricted to female students in Ahvaz, which limits generalizability to other genders or cultural contexts. Future research should include male students and diverse populations to enhance applicability. The small sample size (n=45) may have constrained statistical power, suggesting a need for larger-scale studies. Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures, which may introduce bias; incorporating observational or behavioral assessments could strengthen the findings. Qualitative exploration of participants’ experiences could further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the interventions’ effectiveness. Finally, longer follow-up periods would clarify the durability of these effects beyond one month.

Conclusion

Both resilience training and self-compassion training are significantly effective in improving emotion regulation and frustration tolerance in female students with aggressive tendencies.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the participants, their parents, and the school staff in Ahvaz for their cooperation and support during the study.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Islamic Azad University (code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.480). IRCTID: IRCT20250304064924N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ameri Felihi N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Bavi S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Farashbandi A (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This study received no financial support or funding.

Aggression among adolescents, especially female students, has emerged as a significant global concern, exhibiting a complex interplay with psychological and social health. This behavior, which can manifest as physical, verbal, or relational hostility, often indicates underlying emotional dysregulation and coping deficits [1]. Studies have consistently linked aggressive behavior in youth to a range of adverse outcomes, including academic difficulties, strained peer relationships, and an increased risk of future mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety [2, 3]. In the context of the school environment, aggression disrupts the learning process, compromises school safety, and places a heavy burden on both the students involved and the educational system as a whole [4]. Addressing these behaviors is not merely a matter of discipline but a critical component of promoting well-being and fostering a supportive atmosphere for all students [5]. Therefore, understanding the psychological underpinnings of aggression and developing effective, targeted interventions is a priority for both researchers and practitioners.

Emotion regulation is a crucial skill involving the ability to influence which emotions one has, when one experiences them, and how one expresses them [6]. It is a complex process that includes both conscious and unconscious strategies to manage emotional states. Deficits in emotion regulation are a core component of many psychological disorders, and their link to aggressive behavior is well-documented [7]. Individuals who struggle to regulate their emotions are more likely to react impulsively and with hostility when confronted with challenging situations, as they lack the cognitive and behavioral tools to process their feelings in a constructive manner [8]. Research has shown that teaching adolescents effective emotion regulation strategies can reduce their aggressive tendencies and improve their overall psychological well-being [9].

Frustration tolerance, a closely related construct, refers to an individual’s capacity to cope with situations where goals are blocked or desires are unfulfilled without resorting to extreme emotional or behavioral outbursts [10]. Low frustration tolerance is a hallmark of many aggressive behaviors. When faced with obstacles, individuals with poor frustration tolerance may resort to anger, hostility, and destructive actions rather than employing adaptive problem-solving skills [11]. This can lead to a vicious cycle where a person’s inability to cope with setbacks results in more frequent and intense negative outcomes, further reinforcing their aggressive patterns [12]. Interventions aimed at improving frustration tolerance equip individuals with the resilience and self-control necessary to navigate the inevitable challenges of life without resorting to aggression [13].

Resilience training is a psychoeducational intervention designed to enhance an individual’s capacity to “bounce back” from adversity and stress [14]. It focuses on building internal resources such as problem-solving skills, a positive self-concept, and social support networks. Studies on resilience training have shown its effectiveness in various populations, including college students and workers, leading to reduced stress, improved coping mechanisms, and decreased symptomatology of depression and anxiety [15, 16]. When applied to aggressive adolescents, resilience training can provide a framework for developing adaptive coping strategies, enabling them to respond to challenging situations with greater emotional stability and less impulsivity [17]. By fostering a more resilient mindset, students can learn to view setbacks not as insurmountable obstacles but as opportunities for growth.

Self-compassion training, rooted in compassion-focused therapy, is a distinct yet complementary approach that involves treating oneself with kindness, understanding, and non-judgment, especially during times of failure or inadequacy [18]. It consists of three main components: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification [19]. Research has demonstrated that self-compassion is a powerful antidote to self-criticism, shame, and other negative self-evaluative emotions that often underlie externalizing behaviors like aggression [20]. A compassionate self-view can help individuals accept their flaws and failures, reducing the need to externalize their frustration through aggressive acts [21]. By cultivating self-compassion, individuals can develop a more gentle and accepting relationship with themselves, which, in turn, reduces their emotional reactivity and enhances their ability to cope with difficult feelings.

Despite the established links between aggression and deficits in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, as well as the potential of resilience and self-compassion as therapeutic interventions, there remains a need for comparative research in this area. While previous studies have examined these variables in isolation [14, 20], there is a gap in the literature regarding a direct comparison of the effectiveness of resilience training versus self-compassion training, specifically in the context of addressing aggression in female adolescents. The unique psychological and social pressures faced by this population necessitate targeted interventions that are empirically validated. This study aimed to fill this gap by providing a direct comparison of the two interventions. The primary objective of this research was to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of resilience training and self-compassion training on emotion regulation and frustration tolerance in female middle school students with clinical symptoms of aggression.

Materials and Methods

Design and Participants

This clinical trial, conducted in 2024, employed a pre-test, post-test, and a one-month follow-up design. The statistical population included all female middle school students, aged 13 to 15, with clinical symptoms of aggression in the city of Ahvaz. Using a random cluster sampling method, two educational districts were first selected at random from the city’s districts. From each of these two districts, two schools were randomly chosen, and from each school, two classes were randomly selected. After initial screening, a total of 45 students with clinical symptoms of aggression were identified. These participants were then randomly assigned to one of three groups: a resilience training group (n=15), a self-compassion training group (n=15), and a control group (n=15) that received no intervention.

Inclusion criteria included being a female student aged 13-15, exhibiting clinical symptoms of aggression based on the screening tool, and providing informed written consent from both the student and their parents. Exclusion criteria included missing more than two intervention sessions or having a history of receiving psychological treatment for aggression or related issues. All ethical considerations were carefully observed, including ensuring the confidentiality of all data and providing access to psychological support for all participants after the study was concluded.

Procedure

Following the random assignment of participants, a pre-test was administered to all three groups. The experimental groups then participated in their respective interventions. Resilience training was conducted over 10 weekly sessions of 75 minutes each (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the resilience training sessions

The compassion-focused therapy was implemented in 8 weekly sessions of 90 minutes (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of the self-compassion training sessions

The control group received no treatment during this period. After the interventions were completed, a post-test was administered to all three groups, followed by a one-month follow-up assessment to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the interventions.

Instrument

Affective Control Scale (ACS): Emotion regulation was measured using the 42-item ACS developed by Williams et al. [22]. This instrument consists of four components: anger, depressed mood, anxiety, and positive affect, and it is rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Higher total scores indicate better emotional control. The questionnaire has demonstrated strong validity and reliability; in a previous Persian-language study, its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.76 [23], and in the present study, the value was found to be 0.79.

Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS): Frustration tolerance was assessed using the FDS developed by Harrington in 2005. This instrument contains 35 items across four components, which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. It measures an individual’s ability to cope with obstacles and setbacks on the path to achieving their goals. Higher scores on this questionnaire indicate a greater capacity for frustration tolerance [24]. The reliability of this questionnaire in a previous Persian study was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 [25], and in the current study, it was 0.87.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27 software. The primary analytical method was repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was used to compare the changes in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores across the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases for all three groups. Prior to analysis, data were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming that emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores approximated a normal distribution. Homogeneity of variances was verified via Levene’s test. These findings supported the use of repeated measures ANOVA for subsequent analyses.

Findings

The study included 45 female middle school students aged 13 to 15 years. The mean age across groups was approximately 14 years (14.1±0.7), with no significant differences in age distribution, ensuring comparability among the groups.

At the pre-test, the groups showed comparable scores for emotion regulation and frustration tolerance. Post-intervention, both experimental groups demonstrated significant improvements in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, which were sustained at follow-up, while the control group showed minimal change (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean emotion regulation and frustration tolerance scores across study phases

Significant main effects of time were observed for both emotion regulation and frustration tolerance (p<0.001). Significant time×group interactions were also found (p<0.001), indicating differential changes across groups over time. Group main effects were significant (p<0.001), suggesting variations in intervention efficacy (Table 4).

Table 4. Repeated measures ANOVA results for emotion regulation and frustration tolerance (p-Value=0.001)

For emotion regulation, significant improvements from pre-test to post-test and follow-up were observed in both the resilience (p<0.001) and self-compassion groups (p<0.001), with no significant change in the control group. Similarly, frustration tolerance improved significantly in both experimental groups (p<0.001), but not in the control group (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons of emotion regulation and frustration tolerance across study phases

No significant differences were found between the resilience and self-compassion groups at any phase, indicating comparable efficacy (Table 6).

Table 6. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons of group differences in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance

Discussion

This study investigated the comparative effectiveness of resilience and self-compassion training on emotion regulation and frustration tolerance among female middle school students with clinical symptoms of aggression. Both interventions significantly enhanced emotion regulation and frustration tolerance compared to the control group, with effects sustained at the one-month follow-up. Notably, no significant differences were observed between the resilience and self-compassion groups, suggesting comparable efficacy. These findings align with and extend prior research, offering valuable insights into psychological interventions for adolescent aggression.

The effectiveness of resilience training in improving emotion regulation and frustration tolerance is consistent with existing literature. Previous studies have shown that resilience training enhances coping strategies, reduces stress, and mitigates symptoms of anxiety and depression in various populations [15, 16, 26]. For instance, Steinhardt and Dolbier [26] found that resilience interventions improve adaptive coping, which aligns with our observation of enhanced emotional control and frustration tolerance. This effect may be attributed to the intervention’s focus on cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, and social support, which equip students to manage stressors without resorting to impulsive or aggressive behaviors [27]. By fostering a mindset that views challenges as opportunities for growth, resilience training likely enhances adolescents’ ability to regulate emotions and tolerate frustration, thereby reducing aggressive tendencies [14].

Similarly, self-compassion training yielded significant improvements in emotion regulation and frustration tolerance, corroborating prior research [20, 28]. Self-compassion, which encompasses self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, provides a framework for adolescents to process negative emotions without self-criticism or over-identification [19]. Abdollahi et al. [28] demonstrated that self-compassion moderates the relationship between stress and aggression, a finding supported by our results, in which participants exhibited reduced emotional reactivity and improved coping with setbacks. This may stem from self-compassion’s ability to create a non-judgmental internal space, allowing students to accept their emotional experiences and respond adaptively [21]. Studies by Wang et al. [29] and Guan et al. [30] further suggest that self-compassion mitigates externalizing behaviors by reducing perceived stress and fostering self-acceptance, which is particularly relevant for adolescents navigating social and identity-related challenges.

The absence of significant differences between the two interventions is a critical finding, suggesting that resilience and self-compassion training may target overlapping psychological mechanisms. Both approaches emphasize emotional awareness and adaptive coping, albeit through different lenses: resilience training focuses on building internal and external resources, while self-compassion promotes self-kindness and mindfulness [18]. For example, the mindfulness component of self-compassion training parallels the emotional awareness fostered in resilience training, potentially explaining their comparable outcomes [17, 19]. This convergence suggests that the interventions share core processes, such as enhancing self-regulation and reducing emotional reactivity, which are pivotal in addressing aggression [7, 9]. The flexibility to choose either intervention based on individual or contextual needs is a practical implication for clinicians and educators.

These findings have significant implications for school-based mental health programs. Given the detrimental impact of aggression on academic performance, peer relationships, and school climate [4, 5], implementing resilience or self-compassion training could proactively address these issues. Schools could integrate these interventions into counseling programs or curricula, tailoring delivery to suit diverse student populations. The sustained effects at follow-up underscore the potential for long-term benefits, supporting the adoption of such programs to foster psychological well-being and reduce aggressive behaviors.

This study underscores the efficacy of resilience and self-compassion training in enhancing emotion regulation and frustration tolerance among female students with aggressive tendencies. The comparable effectiveness of these interventions highlights their potential as interchangeable tools in clinical and educational settings. By addressing the psychological underpinnings of aggression, these interventions offer promising avenues for promoting mental health and fostering adaptive coping in adolescents.

The results suggest that both approaches can serve as valuable and interchangeable psychological interventions for mitigating aggression and promoting mental well-being in the adolescent population. The similar outcomes indicate that their underlying mechanisms, which likely include enhancing emotional awareness and acceptance, are potent drivers of positive and lasting change in these key psychological skills.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations. The sample was restricted to female students in Ahvaz, which limits generalizability to other genders or cultural contexts. Future research should include male students and diverse populations to enhance applicability. The small sample size (n=45) may have constrained statistical power, suggesting a need for larger-scale studies. Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures, which may introduce bias; incorporating observational or behavioral assessments could strengthen the findings. Qualitative exploration of participants’ experiences could further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the interventions’ effectiveness. Finally, longer follow-up periods would clarify the durability of these effects beyond one month.

Conclusion

Both resilience training and self-compassion training are significantly effective in improving emotion regulation and frustration tolerance in female students with aggressive tendencies.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the participants, their parents, and the school staff in Ahvaz for their cooperation and support during the study.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Islamic Azad University (code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.480). IRCTID: IRCT20250304064924N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ameri Felihi N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Bavi S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Farashbandi A (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: This study received no financial support or funding.

Keywords:

Resilience [MeSH], Self-Compassion [MeSH], Emotion Regulation [MeSH], Aggression [MeSH], Students [MeSH]

References

1. Yu S, Ma Y, Chao L, Jiang L. Aggressive behavior in adolescent patients with mental disorders: What we can do. Transl Pediatr. 2024;13(12):2183-92. [Link] [DOI:10.21037/tp-24-330]

2. Zeraatkar H, Moradi A. The effect of problem-solving skills training based on storytelling on different levels of aggressive behaviors in students. J Child Ment Health. 2019;6(2):68-80. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jcmh.6.2.7]

3. Voulgaridou I, Kokkinos CM. Relational aggression in adolescents across different cultural contexts: A systematic review of the literature. Adolesc Res Rev. 2023;8(4):457-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40894-023-00207-x]

4. Salimi N, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Rezapur-Shahkolai F, Hamzeh B, Roshanaei G, Babamiri M. Aggression and its predictors among elementary students. J Inj Violence Res. 2019;11(2):159-70. [Link] [DOI:10.5249/jivr.v11i2.1102]

5. Pinchak NP. A paradox of school social organization: Positive school climate, friendship network density, and adolescent violence. J Youth Adolesc. 2024;53(11):2623-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10964-024-02034-2]

6. Amani M, Kazemi SS, Nazari F. Relationship between maladaptive daydreaming and psychological distress in nurses; The moderating role of emotion regulation. J Clin Care Skill. 2025;6(1):11-6. [Link]

7. Nguyen A, Grummitt L, Barrett EL, Bailey S, Gardner LA, Champion KE, et al. The relationship between emotion regulation and mental health in adolescents: Self-compassion as a moderator. Ment Health Prev. 2025;38:200430. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mhp.2025.200430]

8. Alarcón-Espinoza M, Samper P, Anguera MT. Emotional regulation in the classroom: Detection of multiple cases from systematic observation. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1330941. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330941]

9. Gutiérrez-Cobo MJ, Megías-Robles A, Gómez-Leal R, Cabello R, Fernández-Berrocal P. Emotion regulation strategies and aggression in youngsters: The mediating role of negative affect. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e14048. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14048]

10. Simona T, Hortensia BC, Gabriel R. Frustration intolerance scale for students. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2025;32(1):e70028. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.70028]

11. Ruiz-Ortega AM, Berrios-Martos MP. The role of emotional intelligence and frustration intolerance in the academic performance of university students: A structural equation model. J Intell. 2025;13(8):101. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jintelligence13080101]

12. Vahhab M, Latifi Z, Marvi M, Soltanizadeh M, Loyd A. Effects of self-healing training on perfectionism and frustration tolerance in mothers of single-parent students. J Gen Psychol. 2024;151(3):374-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00221309.2023.2275305]

13. Mousavi S, Heidari A, Safarzadeh S, Asgari P, Talebzadeh Shoushtari M. The effectiveness of emotional schema therapy on self-regulation and frustration tolerance in female students with exam anxiety. Womens Health Bull. 2024;11(3):145-52. [Link]

14. Ketelaars E, Gaudin C, Flandin S, Poizat G. Resilience training for critical situation management. An umbrella and a systematic literature review. Saf Sci. 2024;170:106311. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106311]

15. Joyce S, Shand F, Tighe J, Laurent SJ, Bryant RA, Harvey SB. Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e017858. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017858]

16. Sanayi F, Jazayeri R, Fatehizade M. Developing a student's resilience training model based on the lived experiences of resilient students: A qualitative study. Clin Psychol Stud. 2024;14(52):77-116. [Persian] [Link]

17. Nemati S, Badri Gargari R, Vahedi S, Mirkazempour MH. Mindfulness-based resilience training on the psychological well-being of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Dev Med Educ. 2023;12(1):1. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/rdme.2023.33099]

18. Neuenschwander R, Von Gunten FO. Self-compassion in children and adolescents: A systematic review of empirical studies through a developmental lens. Curr Psychol. 2024;44(2):755-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12144-024-07053-7]

19. Gutiérrez-Carmona A, González-Pérez M, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ortega-Galán AM, Henríquez D. Effectiveness of compassion training on stress and anxiety: A pre-experimental study on nursing students. Nurs Rep. 2024;14(4):3667-76. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nursrep14040268]

20. Parvardeh M, Abbasi M, Ghadampour E. The effectiveness of self-compassion training on social-emotional competence in girl students with suicidal ideation. Womens Health Bull. 2025;12(3):198-205. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/tbj.v24i2.19664]

21. Dai M, Liu G. Intervention effect of mindful self-compassion training on adolescents' psychological stress during the pandemic. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51(11):2564-72. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v51i11.11174]

22. Williams KE, Chambless DL, Ahrens A. Are emotions frightening? An extension of the fear of fear construct. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(3):239-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00098-8]

23. Foroughi AA, Parvizifard A, Sadeghi K, Moghadam AP. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021;43(2):101-7. [Link] [DOI:10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0106]

24. Harrington N. The frustration discomfort scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2005;12(5):374-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.465]

25. Mousavi R, Fatemi FS, Shanazi Y. The relationship between frustration tolerance and approval motivation with emotional adjustment of female students. J Couns Res. 2020;19(73):170-89. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jcr.19.73.170]

26. Steinhardt M, Dolbier C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(4):445-53. [Link] [DOI:10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454]

27. Steensma H, Heijer MD, Stallen V. Research Note: Effects of resilience training on the reduction of stress and depression among dutch workers. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2006;27(2):145-59. [Link] [DOI:10.2190/IQ.27.2.e]

28. Abdollahi A, Gardanova ZR, Ramaiah P, Zainal AG, Abdelbasset WK, Asmundson GJG, et al. Moderating role of self-compassion in the relationships between the three forms of perfectionism with anger, aggression, and hostility. Psychol Rep. 2023;126(5):2383-402. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00332941221087911]

29. Wang T, Xiao Q, Wang H, Hu Y, Xiang J. Self-compassion defuses the aggression triggered by social exclusion. Psych J. 2024;13(6):1014-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pchj.774]

30. Guan F, Zhan C, Li S, Tong S, Peng K. Effects of self-compassion on aggression and its psychological mechanism through perceived stress. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):667. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40359-024-02191-w]