Volume 6, Issue 2 (2025)

J Clinic Care Skill 2025, 6(2): 89-95 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.KAUMS.NUHEPM.REC.1403.015

History

Received: 2025/05/16 | Accepted: 2025/06/28 | Published: 2025/07/2

Received: 2025/05/16 | Accepted: 2025/06/28 | Published: 2025/07/2

How to cite this article

Mousavi S, Hosseinian M, Rezaei M. Nurses’ Venipuncture Skills and Related Factors in Kashan University of Medical Sciences’ Hospitals. J Clinic Care Skill 2025; 6 (2) :89-95

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-419-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-419-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Medical Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

2- Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

3- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

2- Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

3- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (525 Views)

Introduction

A nurse is an individual skilled in the scientific principles and professional competencies of patient care, treatment, and education, and serves as a member of the healthcare team in hospitals and clinics [1]. Nursing education planners consider clinical training as the most essential component of nursing education, through which nurses acquire the necessary clinical competence [2]. One of the major duties of nurses in Iran is venipuncture [1]. The insertion of an intravenous catheter, commonly referred to as venipuncture, is an important diagnostic and therapeutic procedure performed using a peripheral venous catheter to provide access for the administration of fluids, electrolytes, blood products, intravenous medications, as well as parenteral nutrition for patients with impaired oral intake. This procedure is invasive and often stressful and painful for many patients [3]. In fact, venipuncture is among the most frequent and painful invasive nursing procedures and is regarded as one of the most anxiety-provoking experiences of illness and hospitalization [4]. It is estimated that nearly 80% of hospitalized patients undergo venipuncture for intravenous drug administration or fluid therapy [3]. Approximately 40% of all medications and fluids are administered intravenously [5], highlighting the critical importance of nursing proficiency in this field.

The failure rate of correct venipuncture and subsequent proper catheter care is relatively high, with the most common cause being initial unsuccessful cannulation (34%). In many cases, successful venipuncture on the first attempt is unlikely and requires multiple attempts [6]. On the other hand, despite the widespread use of peripheral catheters, their application may lead to complications for patients. Such complications can disrupt treatment, impair intravenous fluid flow, and waste healthcare staff time by necessitating catheter reinsertion [7]. The study by Whalen et al. (2017) indicates that difficult peripheral venous access poses tangible threats to patient safety and leads to increased resource utilization (equipment and staff), thereby contributing to both time and cost inefficiencies [8].

Complications arising from inadequate proficiency in peripheral catheter insertion include hematoma, vessel rupture, extravasation of medications or fluids, fluid retention, air embolism, bleeding, local catheter-site infection, catheter-related disease transmission, pain due to insertion and removal, and allergic reactions to fixation adhesives [7–8]. Nursing expertise in venipuncture reduces the duration and frequency of cannulation attempts, decreases the cost and consumption of supplies, and improves nurses’ speed and efficiency while enhancing patient comfort and safety [6]. To reduce complication rates, numerous studies have focused on catheter insertion techniques, proper pre-procedure vascular assessment, continuous post-insertion evaluation, as well as innovations in catheter and dressing design. Nevertheless, failure rates remain high [8].

Although relatively few studies have been conducted on nurses’ venipuncture skills, various supportive and critical perspectives exist. For example, Hosseini et al. (2021) have reported that, based on the OSCE assessment, the venipuncture skills of senior nursing students were rated “excellent” or “good” in 92.31% of cases [9]. In contrast, the study by Brem et al. (2016) in Switzerland, which compares the venipuncture performance of senior nursing students with that of licensed clinical nurses using the OSCE, reveals superior performance and higher average scores among licensed nurses [10]. Similarly, Lund et al. (2012) have demonstrated that while students achieved satisfactory scores in venipuncture during their final OSCE evaluation, their scores declined upon entering clinical practice, likely due to high patient loads, time constraints, and reduced concentration when attending to a large number of patients within limited timeframes [11].

Chen et al. (2022) report that, despite the extensive application of peripheral venous cannulation, an estimated 26–69% of catheters fail prematurely or even immediately after insertion [12]. Additionally, Kache et al. (2022) have found out that between 53.4% and 60.5% of inserted catheters failed before the standard 72-hour duration, requiring reinsertion [13]. Nurses commonly encounter challenges when inserting peripheral intravenous catheters in both adults and children. Multiple factors such as small, fragile, or hidden veins; vein deterioration due to dehydration; age; underlying diseases; and anxiety of both patient and nurse can complicate vascular access [10–13].

Accordingly, given the contradictory findings in this field, the numerous challenges faced by nurses in venipuncture, and the multiple factors influencing the accurate execution of this procedure, the present study aimed to determine the clinical competence of nurses in venipuncture and the associated factors in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences in 2024.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive–observational study was conducted in 2024 in hospitals located in Kashan. The study population consisted of nurses working in five hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences. The sample size was determined based on the study by Ahlin et al. [14], considering a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error, which resulted in 236 participants. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate, the final sample size was calculated to be 253. Sampling was performed using a non-probability quota method. After identifying the total number of nurses in each hospital, the sample size for each hospital was determined, and participants were then randomly selected from different wards. Nurses working in medical, surgical, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and emergency wards were included. Specialized units such as CCU, ICU, and hemodialysis, as well as injection units for specific patients, were excluded due to potential interference with the evaluation of venipuncture skills.

Inclusion criteria were having at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing, a minimum of six months of clinical experience, performing venipuncture on conscious patients without edema, and venipuncture sites limited to both hands, dorsum of the hand, inner forearm, and antecubital fossa. Exclusion criteria included occurrence of unexpected complications or life-threatening conditions during venipuncture requiring termination of the procedure for patient safety, incomplete observation of the procedure by the evaluator, incomplete checklists, or missing data.

Data collection instruments included a) A demographic questionnaire for nurses, covering ward of employment, gender, age, marital status, education level, employment status, work experience, and time of skill assessment. Nurses’ stress levels during venipuncture were also measured using a 0–10 Numeric Visual Analogue Scale; b) A patient information questionnaire including gender, age, history of underlying diseases, length of current hospitalization, and presence of a companion or parent during venipuncture; c) A researcher-developed clinical venipuncture skills checklist. This 43-item checklist was designed by reviewing OSCE venipuncture checklists from Iranian medical universities and the most recent globally accepted OSCE checklist [15]. Content validity was assessed by 10 faculty members of the Nursing Department at Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Using Lawshe’s CVR method, three items with a score below 0.62 were eliminated [16]. Content Validity Index (CVI) analysis indicated that all remaining items had CVI>0.79 and were approved [16].

For reliability, two evaluators simultaneously observed nurses during venipuncture at the bedside. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated for 40 items, showing acceptable inter-rater reliability. The final 40-item checklist included five stages of preparation, vein selection, establishing venous access, cannula flushing, and completion of the procedure. Each item had two response options of “performed” (score 1) or “not performed” (score 0). The total score ranged from 0 to 40. Skill levels were categorized as: <20=poor, 20-28=moderate, 29-36=good, and >36=very good/excellent. Additionally, three complementary questions assessed number of attempts required, presence of a companion during venipuncture, and duration of the procedure (minutes).

For data collection, the study objectives were explained to participants, who then provided written informed consent. They were assured that participation was voluntary and their personal information would remain confidential. Questionnaires were anonymous. If any participant withdrew, another nurse was randomly selected as replacement. Nurses completed demographic and occupational questionnaires in a quiet, private environment. Patient-related data were collected mainly via direct interview with the patient and, in some cases, with the attending nurse.

Next, nurses’ venipuncture skills were evaluated using the checklist through direct observation at the bedside. The observer recorded nurse behaviors without intervening. Each nurse was assessed only once. To minimize observer effect, evaluators entered the ward several days before assessment to normalize their presence. Strategies such as assisting nurses with routine tasks, similar to nursing interns, were used to increase collaboration and reduce the impact of observation on performance.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the normality of quantitative parameters. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage for qualitative parameters; mean and standard deviation for quantitative parameters) were used to describe data. To compare mean skill scores across demographic parameters, independent t-test, ANOVA, and Pearson correlation coefficient were employed. Multiple linear regression with stepwise method was applied to examine the association between venipuncture skill scores and demographic factors. Parameters with a p-value<0.15 in univariate analysis were entered into the regression model. A significance level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Health, and Paramedicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Participants were fully informed of the study objectives and provided written consent. Researchers committed to preserving confidentiality, privacy, and anonymity. Personal data were strictly protected and only reported in aggregate form in publications. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Findings

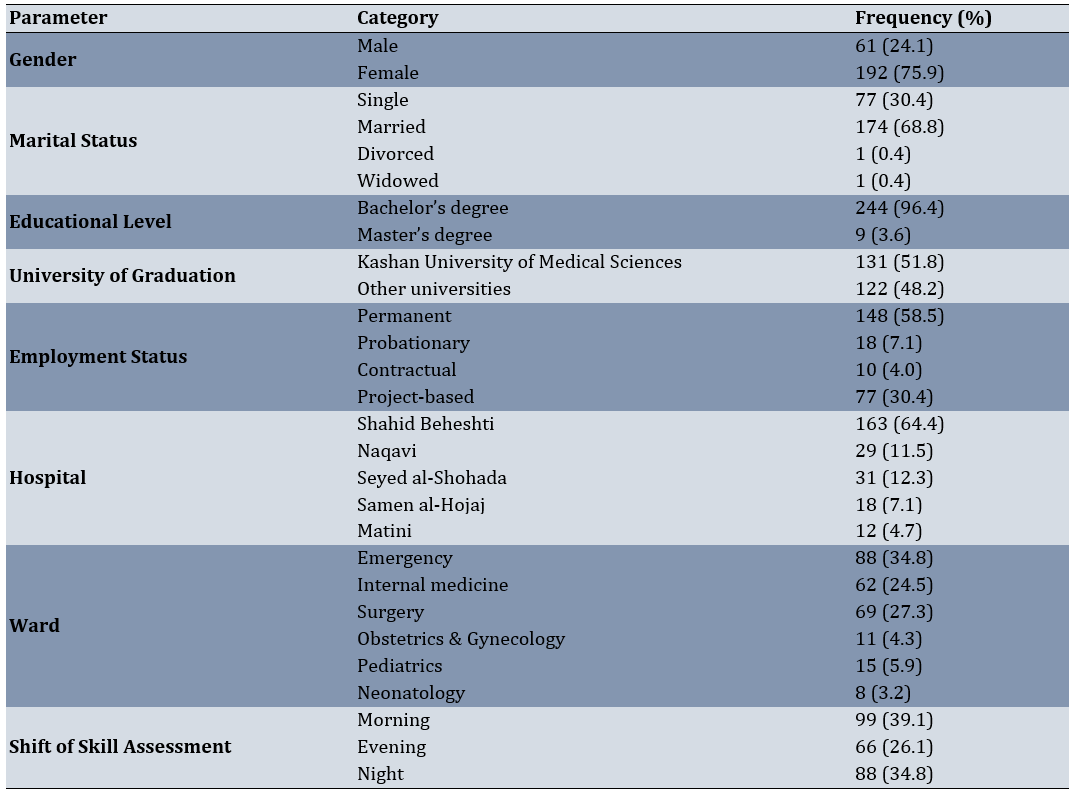

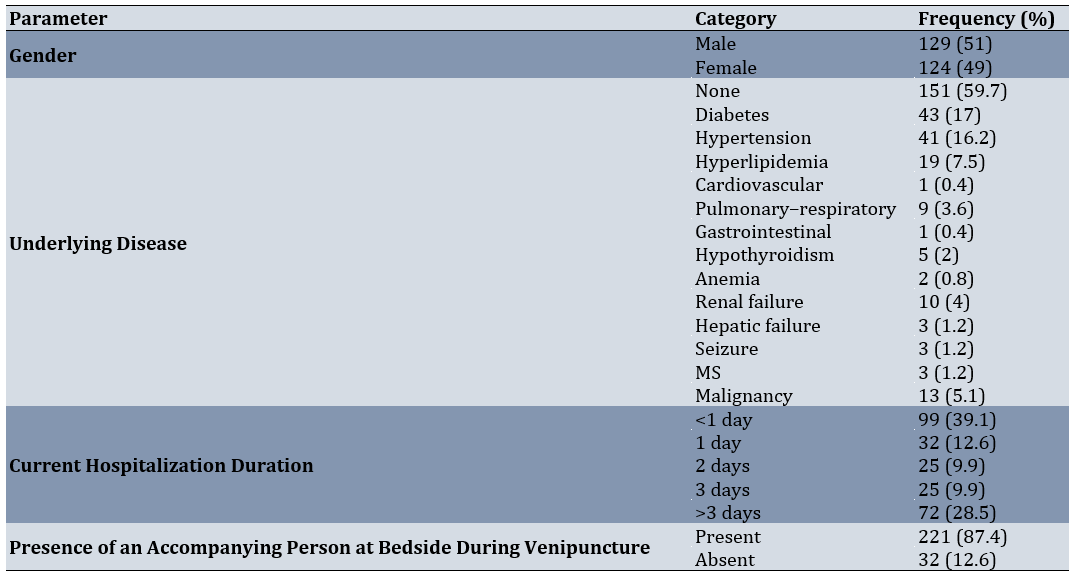

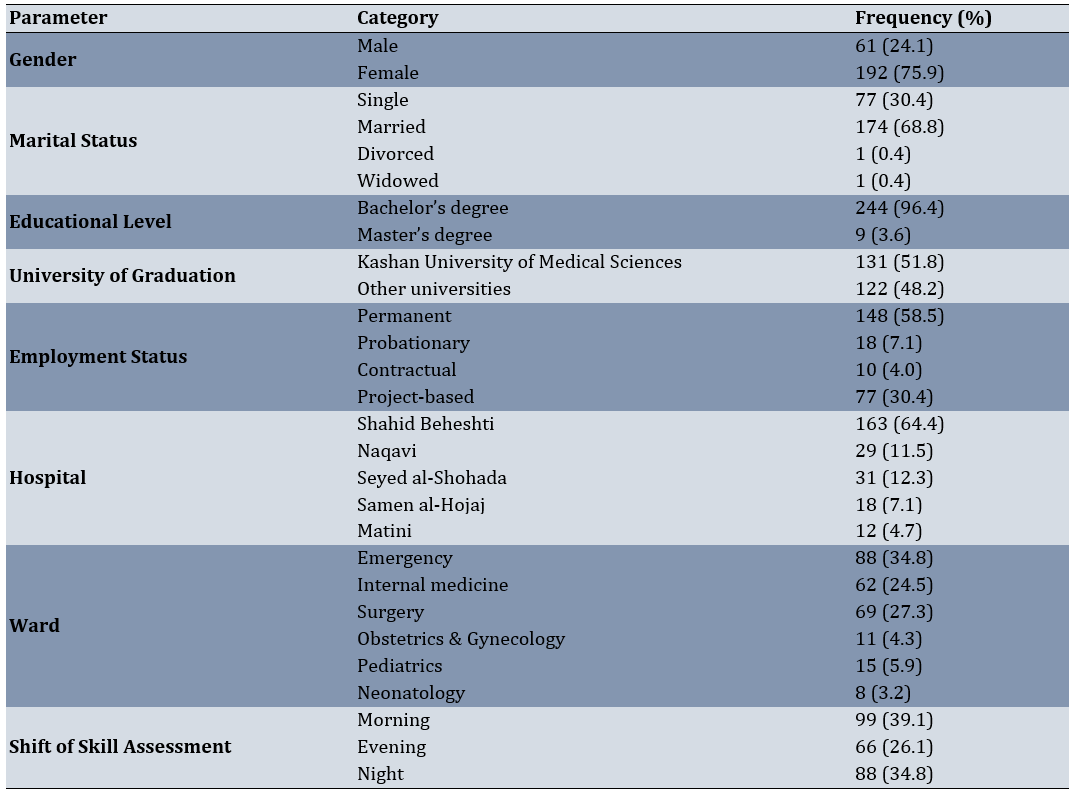

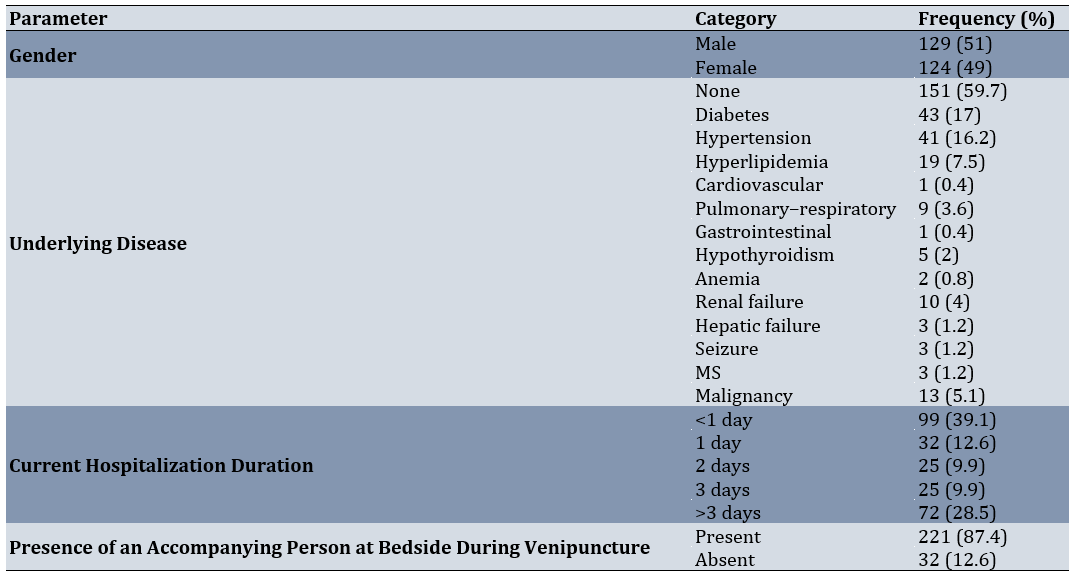

In this study, 253 nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences were examined. The findings showed that the mean age of nurses was 32.04±7.51 years. The majority of nurses were married (68.8%). The mean work experience of the studied nurses was 8.74 ± 7.06 years. The mean job stress score of the nurses, measured using the VAS scale, was 4.58 ± 3.16 with a range of 0 to 10 (Table 1). The results also indicated that the mean age of patients was 41.10 ± 23.46 years, with diabetes and hypertension being the most common underlying diseases. Most patients undergoing venipuncture had been hospitalized for less than one day (39.1%). In addition, nearly 90% of patients had a companion present during venipuncture (Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the studied nurses

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of patients undergoing venipuncture in this study

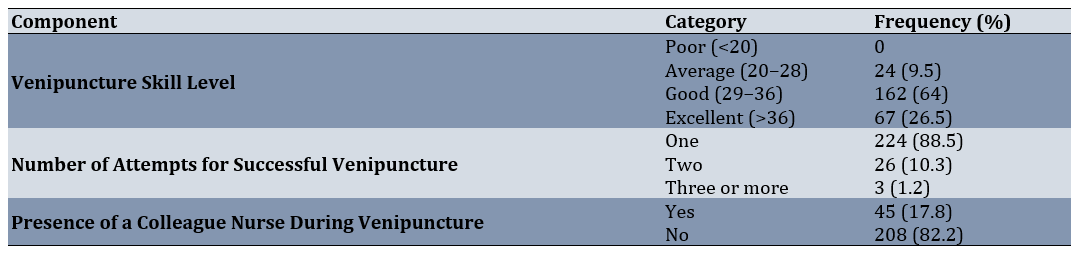

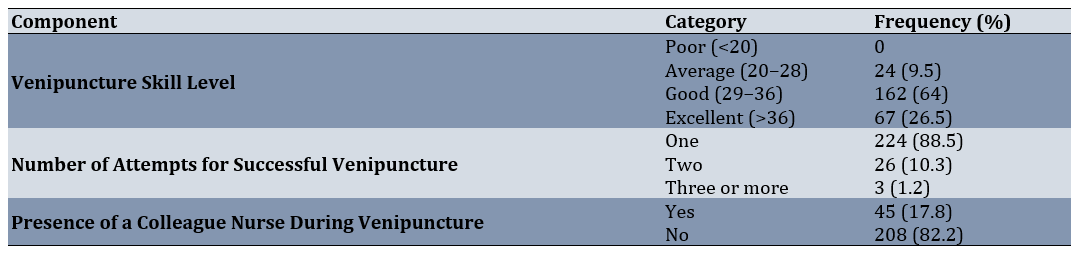

The mean score for the different components of venipuncture skills among nurses were as follows: the preparation stage scored 5.39±1.66 (range:0-7), preparation and selection of the appropriate vein scored 6.25±1.37 (range: 3.43–8), establishment of the intravenous line scored 16.59 ± 0.71 (range: 13–17), cannula flushing scored 1.31±0.64 (range: 0–2), and the final steps of the procedure scored 4.13±1.41 (range: 0–6). The total venipuncture skill score of nurses was 33.68 ± 3.73, ranging from 20.30 to 40.

The mean duration of venipuncture (from arrival at the bedside to completion) varied by ward: in the emergency ward, it was 3.99±3.61 minutes; in internal ward, 6.69±4.02 minutes; in surgery, 6.46±4.34 minutes; in obstetrics and gynecology, 5.27±1.68 minutes; in pediatrics, 12.07±7.10 minutes; and in neonatology, 12.37±8.58 minutes (Table 3).

Table3. Venipuncture skill levels and related parameters among nurses

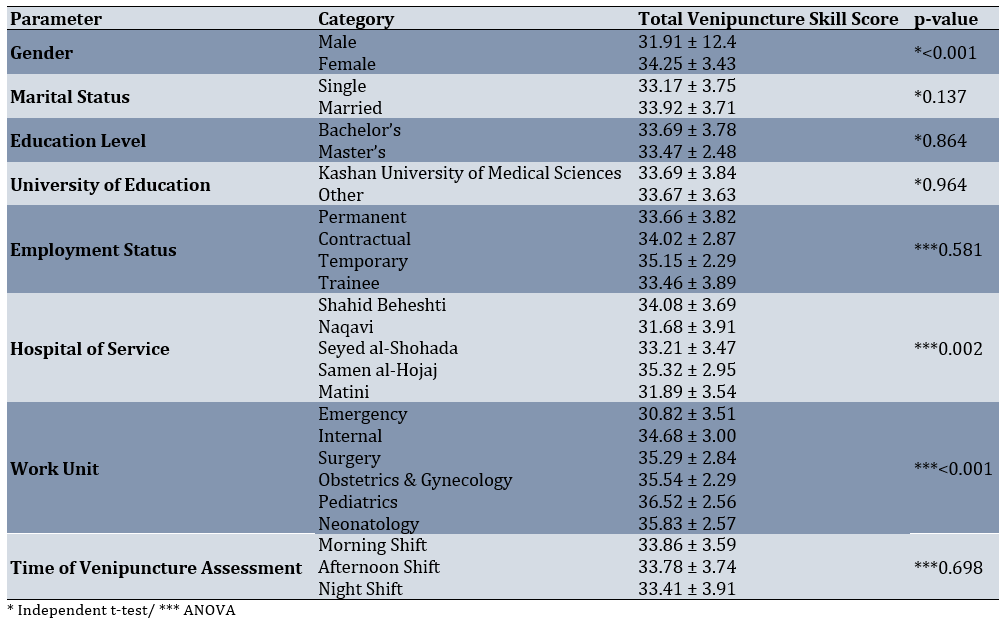

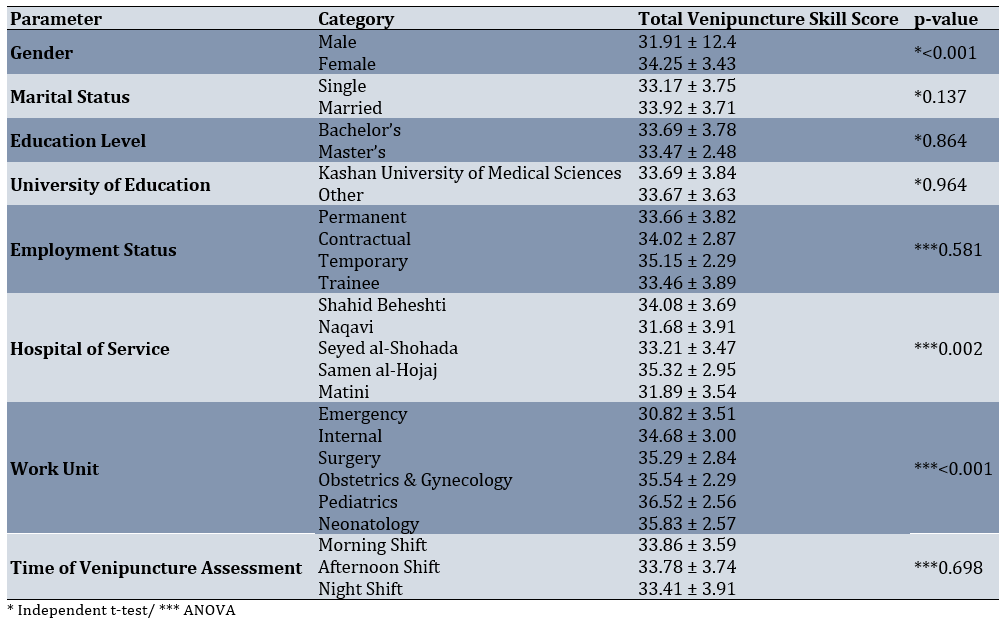

In the univariate analysis of venipuncture skill and demographic parameters related to both nurses and patients, statistically significant associations (p<0.05) were observed between nurse gender, hospital, ward of employment, patient length of stay, presence of a companion at the bedside and presence of a colleague nurse (Table 4 & 5). The results of the Pearson correlation test showed that there was no statistically significant correlation between the nurses’ age (r=0.042, p=0.506) and work experience (r=0.049, p=0.441) with their venipuncture skill. Nevertheless, the results of this test showed that there was a statistically significant correlation between occupational job stress and nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=0.184, p=0.003; Table 4).

Table 4. Total venipuncture skill scores by parameters related to the nurses

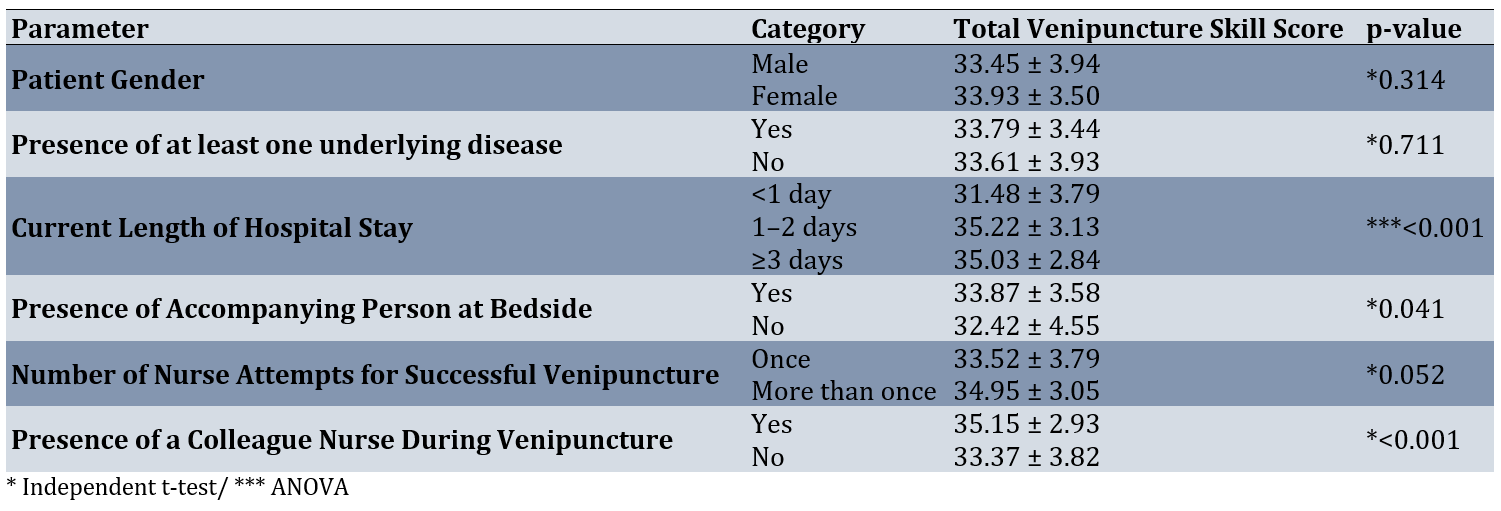

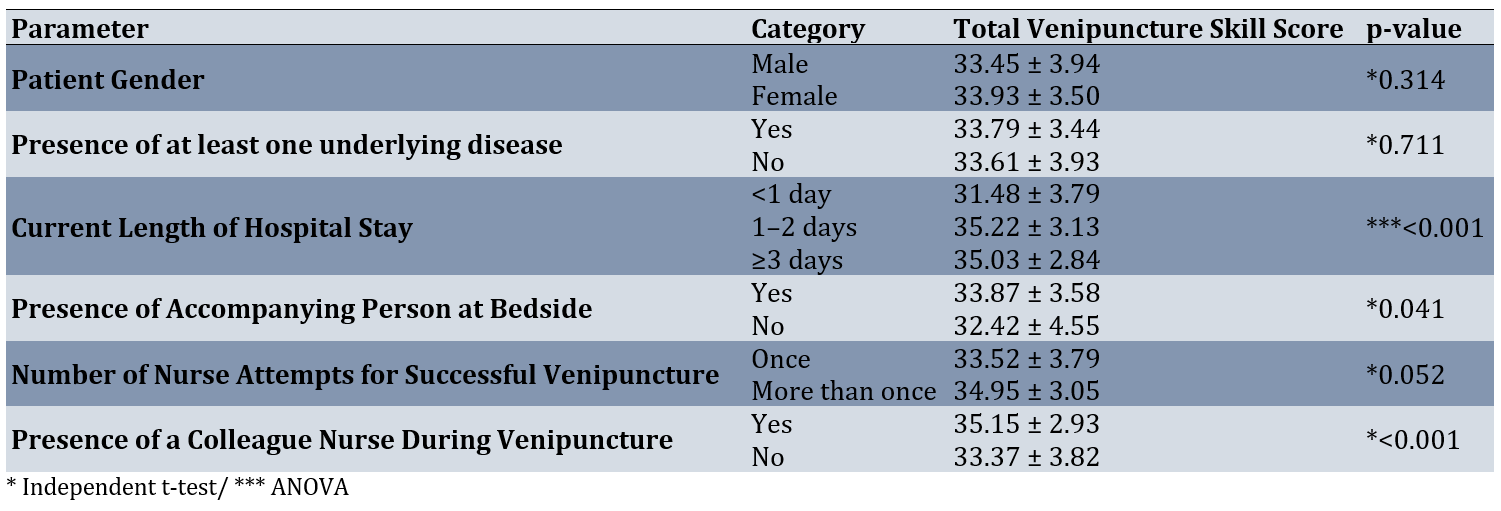

The results of the Pearson correlation test indicated that there was no statistically significant correlation between the patient's age and the nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=-0.058, p= 0.360). However, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the duration of venipuncture and the nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=0.242, p<0.001; Table 5).

Table 5. Total venipuncture skill scores by parameters related to the patients

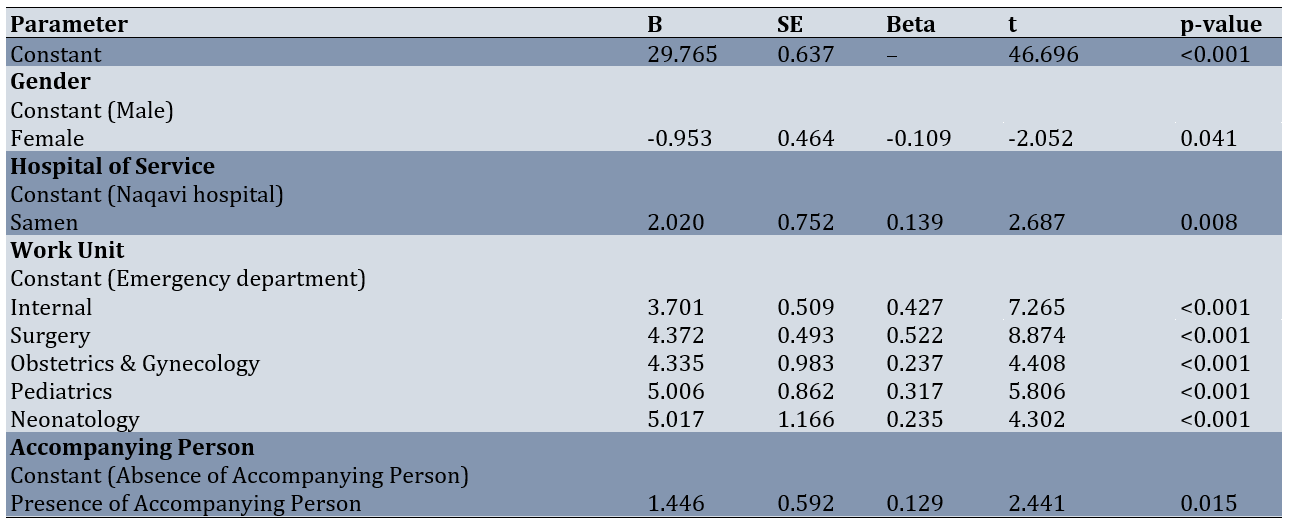

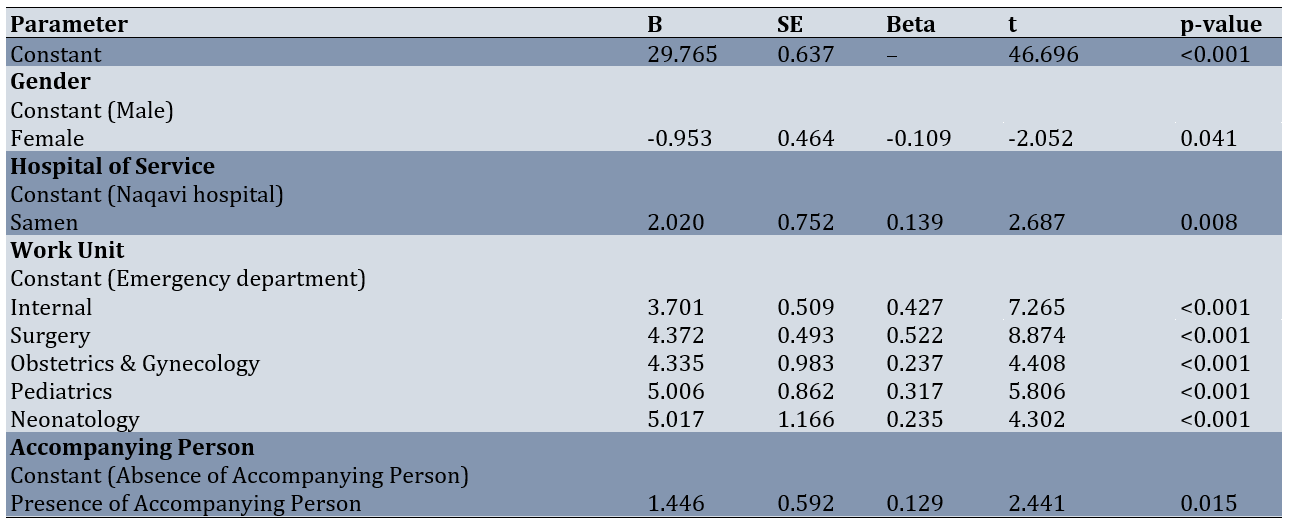

According to ANOVA results, the model fit was acceptable and statistically significant at an error level of <0.001. The coefficient of determination indicated that four parameters collectively explained 35% of the variance in venipuncture skill scores. Furthermore, the mean venipuncture skill score was higher among female nurses compared to male nurses. Nurses working at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital scored higher compared to those at Naqavi Hospital. Conversely, mean venipuncture skill scores among nurses in the emergency ward were lower than in other wards. Finally, nurses achieved higher skill scores when a patient’s companion was present during venipuncture compared to when no companion was present (Table 6).

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis of factors affecting venipuncture skill

Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that the nurses’ venipuncture skills were at a “desirable” level, consistent with the global standards of developed countries as well as the standards defined by the World Health Organization and the National Health Service of the UK. Data analysis in this study showed that nurses received the lowest scores during the preparatory stages, particularly in adhering to hand hygiene, and also in the final stages of the procedure, including education about complications such as phlebitis and thrombophlebitis, and in thanking the patient or their companion. Conversely, the highest scores were achieved in the stages of preparation, selecting an appropriate vein, and establishing the intravenous line. Training on hygiene practices is considered a fundamental aspect of healthcare staff education to prevent disease transmission [17]. Etafa et al. (2020), in their study at Wollega University, Ethiopia, have reported that nursing students correctly adhere to hand hygiene only 77% of the time [18], whereas Hernon et al. (2024) have found out that nurses disinfected their hands in 91.7% of initial procedures and 89% at the end [19]. Comparing Hernon’s findings in Ireland (2024) with the present study suggests that nurses in this study adhered more closely to venipuncture standards.

The present study revealed that 88.5% of nurses succeeded in venipuncture on the first attempt, 10.3% on the second attempt, and 1.2% on the third attempt. In Jacobs’s (2022) study in the USA, 95% of nurses succeed on the first attempt and 5% on the second attempt [20]. In the current study, in 17.8% of cases, a colleague nurse was present at the patient’s bedside during venipuncture, primarily in the pediatric and neonatal wards due to protocols for restraining and calming children. Additionally, another nurse assisted in collecting blood sample tubes from freshly drawn samples. Tomás-Jiménez (2021) recommends that for pediatric and neonatal venipuncture, a colleague nurse should hold the limb in the correct position to increase success rates and ensure proper technique [21].

In this study, the average duration of venipuncture from the nurse’s arrival at the patient’s bedside to leaving was approximately 6.13 minutes, with averages under 4 minutes in the emergency department, under 7 minutes in internal medicine, and under 6.5 minutes in surgery. The longest time was in the pediatric ward, averaging 12 minutes due to the more challenging process of persuading and calming the child, occasionally extending up to 25 minutes. In Jones et al.’s (2016) study across four hospitals in Canada with 110 venipuncture specialists, the average venipuncture duration ranged from 3.2 to 7.6 minutes [22], while Leung et al. (2006) in Hong Kong report an average of 10.2 minutes [23]. Furthermore, Wong et al. (2023) have reported an average duration of 3.47 to 7.39 minutes for children aged 4 to 12 in a pediatric hospital ward in China [24]. As noted in the findings, due to the more complex venipuncture procedures in neonates and adherence to special protocols, the average venipuncture time in the neonatal ward in the present study was 12.5 minutes.

The findings indicated that the mean venipuncture skill score was higher in female nurses than male nurses, although further research is required in this regard. It appears that female nurses may have greater motivation to learn and practice clinical and practical skills and devote more time to these tasks. Additionally, the mean venipuncture skill score of nurses at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital was higher than that of Naqavi Hospital. This may be due to the more spacious and newly built facilities at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital, easier access to materials and supplies at patient bedsides, and a lower workload for nurses, which could improve venipuncture skill quality. Moreover, the mean skill score across the five hospitals examined showed that the emergency department had lower scores compared to other wards. This may be due to the urgent and emergency nature of care in the emergency department, where nurses may have insufficient time to provide high-quality care. Additionally, an imbalanced patient-to-nurse ratio and the high workload of emergency nurses may contribute to this outcome. Conversely, the mean venipuncture skill scores were higher in pediatric and neonatal wards, likely due to the higher sensitivity of procedures in these wards and the greater expertise of nurses working there.

Conclusion

venipuncture standards are adhered to by 90% of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments: The researchers sincerely thank all the esteemed nurses who participated in this study. Appreciation is also extended to the Honorable Research Deputy of Kashan University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support for this research.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics code IR.KAUMS.NUHEPM.REC.1403.015 was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Health, and Paramedical Sciences at Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing is declared by the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Mousavi SMH (First Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Hosseinian M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (25%); Rezaei M (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%)

Fundings: Nothing is declared by the authors.

A nurse is an individual skilled in the scientific principles and professional competencies of patient care, treatment, and education, and serves as a member of the healthcare team in hospitals and clinics [1]. Nursing education planners consider clinical training as the most essential component of nursing education, through which nurses acquire the necessary clinical competence [2]. One of the major duties of nurses in Iran is venipuncture [1]. The insertion of an intravenous catheter, commonly referred to as venipuncture, is an important diagnostic and therapeutic procedure performed using a peripheral venous catheter to provide access for the administration of fluids, electrolytes, blood products, intravenous medications, as well as parenteral nutrition for patients with impaired oral intake. This procedure is invasive and often stressful and painful for many patients [3]. In fact, venipuncture is among the most frequent and painful invasive nursing procedures and is regarded as one of the most anxiety-provoking experiences of illness and hospitalization [4]. It is estimated that nearly 80% of hospitalized patients undergo venipuncture for intravenous drug administration or fluid therapy [3]. Approximately 40% of all medications and fluids are administered intravenously [5], highlighting the critical importance of nursing proficiency in this field.

The failure rate of correct venipuncture and subsequent proper catheter care is relatively high, with the most common cause being initial unsuccessful cannulation (34%). In many cases, successful venipuncture on the first attempt is unlikely and requires multiple attempts [6]. On the other hand, despite the widespread use of peripheral catheters, their application may lead to complications for patients. Such complications can disrupt treatment, impair intravenous fluid flow, and waste healthcare staff time by necessitating catheter reinsertion [7]. The study by Whalen et al. (2017) indicates that difficult peripheral venous access poses tangible threats to patient safety and leads to increased resource utilization (equipment and staff), thereby contributing to both time and cost inefficiencies [8].

Complications arising from inadequate proficiency in peripheral catheter insertion include hematoma, vessel rupture, extravasation of medications or fluids, fluid retention, air embolism, bleeding, local catheter-site infection, catheter-related disease transmission, pain due to insertion and removal, and allergic reactions to fixation adhesives [7–8]. Nursing expertise in venipuncture reduces the duration and frequency of cannulation attempts, decreases the cost and consumption of supplies, and improves nurses’ speed and efficiency while enhancing patient comfort and safety [6]. To reduce complication rates, numerous studies have focused on catheter insertion techniques, proper pre-procedure vascular assessment, continuous post-insertion evaluation, as well as innovations in catheter and dressing design. Nevertheless, failure rates remain high [8].

Although relatively few studies have been conducted on nurses’ venipuncture skills, various supportive and critical perspectives exist. For example, Hosseini et al. (2021) have reported that, based on the OSCE assessment, the venipuncture skills of senior nursing students were rated “excellent” or “good” in 92.31% of cases [9]. In contrast, the study by Brem et al. (2016) in Switzerland, which compares the venipuncture performance of senior nursing students with that of licensed clinical nurses using the OSCE, reveals superior performance and higher average scores among licensed nurses [10]. Similarly, Lund et al. (2012) have demonstrated that while students achieved satisfactory scores in venipuncture during their final OSCE evaluation, their scores declined upon entering clinical practice, likely due to high patient loads, time constraints, and reduced concentration when attending to a large number of patients within limited timeframes [11].

Chen et al. (2022) report that, despite the extensive application of peripheral venous cannulation, an estimated 26–69% of catheters fail prematurely or even immediately after insertion [12]. Additionally, Kache et al. (2022) have found out that between 53.4% and 60.5% of inserted catheters failed before the standard 72-hour duration, requiring reinsertion [13]. Nurses commonly encounter challenges when inserting peripheral intravenous catheters in both adults and children. Multiple factors such as small, fragile, or hidden veins; vein deterioration due to dehydration; age; underlying diseases; and anxiety of both patient and nurse can complicate vascular access [10–13].

Accordingly, given the contradictory findings in this field, the numerous challenges faced by nurses in venipuncture, and the multiple factors influencing the accurate execution of this procedure, the present study aimed to determine the clinical competence of nurses in venipuncture and the associated factors in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences in 2024.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive–observational study was conducted in 2024 in hospitals located in Kashan. The study population consisted of nurses working in five hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences. The sample size was determined based on the study by Ahlin et al. [14], considering a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error, which resulted in 236 participants. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate, the final sample size was calculated to be 253. Sampling was performed using a non-probability quota method. After identifying the total number of nurses in each hospital, the sample size for each hospital was determined, and participants were then randomly selected from different wards. Nurses working in medical, surgical, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and emergency wards were included. Specialized units such as CCU, ICU, and hemodialysis, as well as injection units for specific patients, were excluded due to potential interference with the evaluation of venipuncture skills.

Inclusion criteria were having at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing, a minimum of six months of clinical experience, performing venipuncture on conscious patients without edema, and venipuncture sites limited to both hands, dorsum of the hand, inner forearm, and antecubital fossa. Exclusion criteria included occurrence of unexpected complications or life-threatening conditions during venipuncture requiring termination of the procedure for patient safety, incomplete observation of the procedure by the evaluator, incomplete checklists, or missing data.

Data collection instruments included a) A demographic questionnaire for nurses, covering ward of employment, gender, age, marital status, education level, employment status, work experience, and time of skill assessment. Nurses’ stress levels during venipuncture were also measured using a 0–10 Numeric Visual Analogue Scale; b) A patient information questionnaire including gender, age, history of underlying diseases, length of current hospitalization, and presence of a companion or parent during venipuncture; c) A researcher-developed clinical venipuncture skills checklist. This 43-item checklist was designed by reviewing OSCE venipuncture checklists from Iranian medical universities and the most recent globally accepted OSCE checklist [15]. Content validity was assessed by 10 faculty members of the Nursing Department at Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Using Lawshe’s CVR method, three items with a score below 0.62 were eliminated [16]. Content Validity Index (CVI) analysis indicated that all remaining items had CVI>0.79 and were approved [16].

For reliability, two evaluators simultaneously observed nurses during venipuncture at the bedside. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated for 40 items, showing acceptable inter-rater reliability. The final 40-item checklist included five stages of preparation, vein selection, establishing venous access, cannula flushing, and completion of the procedure. Each item had two response options of “performed” (score 1) or “not performed” (score 0). The total score ranged from 0 to 40. Skill levels were categorized as: <20=poor, 20-28=moderate, 29-36=good, and >36=very good/excellent. Additionally, three complementary questions assessed number of attempts required, presence of a companion during venipuncture, and duration of the procedure (minutes).

For data collection, the study objectives were explained to participants, who then provided written informed consent. They were assured that participation was voluntary and their personal information would remain confidential. Questionnaires were anonymous. If any participant withdrew, another nurse was randomly selected as replacement. Nurses completed demographic and occupational questionnaires in a quiet, private environment. Patient-related data were collected mainly via direct interview with the patient and, in some cases, with the attending nurse.

Next, nurses’ venipuncture skills were evaluated using the checklist through direct observation at the bedside. The observer recorded nurse behaviors without intervening. Each nurse was assessed only once. To minimize observer effect, evaluators entered the ward several days before assessment to normalize their presence. Strategies such as assisting nurses with routine tasks, similar to nursing interns, were used to increase collaboration and reduce the impact of observation on performance.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the normality of quantitative parameters. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage for qualitative parameters; mean and standard deviation for quantitative parameters) were used to describe data. To compare mean skill scores across demographic parameters, independent t-test, ANOVA, and Pearson correlation coefficient were employed. Multiple linear regression with stepwise method was applied to examine the association between venipuncture skill scores and demographic factors. Parameters with a p-value<0.15 in univariate analysis were entered into the regression model. A significance level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Health, and Paramedicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Participants were fully informed of the study objectives and provided written consent. Researchers committed to preserving confidentiality, privacy, and anonymity. Personal data were strictly protected and only reported in aggregate form in publications. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Findings

In this study, 253 nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences were examined. The findings showed that the mean age of nurses was 32.04±7.51 years. The majority of nurses were married (68.8%). The mean work experience of the studied nurses was 8.74 ± 7.06 years. The mean job stress score of the nurses, measured using the VAS scale, was 4.58 ± 3.16 with a range of 0 to 10 (Table 1). The results also indicated that the mean age of patients was 41.10 ± 23.46 years, with diabetes and hypertension being the most common underlying diseases. Most patients undergoing venipuncture had been hospitalized for less than one day (39.1%). In addition, nearly 90% of patients had a companion present during venipuncture (Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the studied nurses

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of patients undergoing venipuncture in this study

The mean score for the different components of venipuncture skills among nurses were as follows: the preparation stage scored 5.39±1.66 (range:0-7), preparation and selection of the appropriate vein scored 6.25±1.37 (range: 3.43–8), establishment of the intravenous line scored 16.59 ± 0.71 (range: 13–17), cannula flushing scored 1.31±0.64 (range: 0–2), and the final steps of the procedure scored 4.13±1.41 (range: 0–6). The total venipuncture skill score of nurses was 33.68 ± 3.73, ranging from 20.30 to 40.

The mean duration of venipuncture (from arrival at the bedside to completion) varied by ward: in the emergency ward, it was 3.99±3.61 minutes; in internal ward, 6.69±4.02 minutes; in surgery, 6.46±4.34 minutes; in obstetrics and gynecology, 5.27±1.68 minutes; in pediatrics, 12.07±7.10 minutes; and in neonatology, 12.37±8.58 minutes (Table 3).

Table3. Venipuncture skill levels and related parameters among nurses

In the univariate analysis of venipuncture skill and demographic parameters related to both nurses and patients, statistically significant associations (p<0.05) were observed between nurse gender, hospital, ward of employment, patient length of stay, presence of a companion at the bedside and presence of a colleague nurse (Table 4 & 5). The results of the Pearson correlation test showed that there was no statistically significant correlation between the nurses’ age (r=0.042, p=0.506) and work experience (r=0.049, p=0.441) with their venipuncture skill. Nevertheless, the results of this test showed that there was a statistically significant correlation between occupational job stress and nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=0.184, p=0.003; Table 4).

Table 4. Total venipuncture skill scores by parameters related to the nurses

The results of the Pearson correlation test indicated that there was no statistically significant correlation between the patient's age and the nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=-0.058, p= 0.360). However, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the duration of venipuncture and the nurses’ venipuncture skill (r=0.242, p<0.001; Table 5).

Table 5. Total venipuncture skill scores by parameters related to the patients

According to ANOVA results, the model fit was acceptable and statistically significant at an error level of <0.001. The coefficient of determination indicated that four parameters collectively explained 35% of the variance in venipuncture skill scores. Furthermore, the mean venipuncture skill score was higher among female nurses compared to male nurses. Nurses working at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital scored higher compared to those at Naqavi Hospital. Conversely, mean venipuncture skill scores among nurses in the emergency ward were lower than in other wards. Finally, nurses achieved higher skill scores when a patient’s companion was present during venipuncture compared to when no companion was present (Table 6).

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis of factors affecting venipuncture skill

Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that the nurses’ venipuncture skills were at a “desirable” level, consistent with the global standards of developed countries as well as the standards defined by the World Health Organization and the National Health Service of the UK. Data analysis in this study showed that nurses received the lowest scores during the preparatory stages, particularly in adhering to hand hygiene, and also in the final stages of the procedure, including education about complications such as phlebitis and thrombophlebitis, and in thanking the patient or their companion. Conversely, the highest scores were achieved in the stages of preparation, selecting an appropriate vein, and establishing the intravenous line. Training on hygiene practices is considered a fundamental aspect of healthcare staff education to prevent disease transmission [17]. Etafa et al. (2020), in their study at Wollega University, Ethiopia, have reported that nursing students correctly adhere to hand hygiene only 77% of the time [18], whereas Hernon et al. (2024) have found out that nurses disinfected their hands in 91.7% of initial procedures and 89% at the end [19]. Comparing Hernon’s findings in Ireland (2024) with the present study suggests that nurses in this study adhered more closely to venipuncture standards.

The present study revealed that 88.5% of nurses succeeded in venipuncture on the first attempt, 10.3% on the second attempt, and 1.2% on the third attempt. In Jacobs’s (2022) study in the USA, 95% of nurses succeed on the first attempt and 5% on the second attempt [20]. In the current study, in 17.8% of cases, a colleague nurse was present at the patient’s bedside during venipuncture, primarily in the pediatric and neonatal wards due to protocols for restraining and calming children. Additionally, another nurse assisted in collecting blood sample tubes from freshly drawn samples. Tomás-Jiménez (2021) recommends that for pediatric and neonatal venipuncture, a colleague nurse should hold the limb in the correct position to increase success rates and ensure proper technique [21].

In this study, the average duration of venipuncture from the nurse’s arrival at the patient’s bedside to leaving was approximately 6.13 minutes, with averages under 4 minutes in the emergency department, under 7 minutes in internal medicine, and under 6.5 minutes in surgery. The longest time was in the pediatric ward, averaging 12 minutes due to the more challenging process of persuading and calming the child, occasionally extending up to 25 minutes. In Jones et al.’s (2016) study across four hospitals in Canada with 110 venipuncture specialists, the average venipuncture duration ranged from 3.2 to 7.6 minutes [22], while Leung et al. (2006) in Hong Kong report an average of 10.2 minutes [23]. Furthermore, Wong et al. (2023) have reported an average duration of 3.47 to 7.39 minutes for children aged 4 to 12 in a pediatric hospital ward in China [24]. As noted in the findings, due to the more complex venipuncture procedures in neonates and adherence to special protocols, the average venipuncture time in the neonatal ward in the present study was 12.5 minutes.

The findings indicated that the mean venipuncture skill score was higher in female nurses than male nurses, although further research is required in this regard. It appears that female nurses may have greater motivation to learn and practice clinical and practical skills and devote more time to these tasks. Additionally, the mean venipuncture skill score of nurses at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital was higher than that of Naqavi Hospital. This may be due to the more spacious and newly built facilities at Samen al-Hojaj Hospital, easier access to materials and supplies at patient bedsides, and a lower workload for nurses, which could improve venipuncture skill quality. Moreover, the mean skill score across the five hospitals examined showed that the emergency department had lower scores compared to other wards. This may be due to the urgent and emergency nature of care in the emergency department, where nurses may have insufficient time to provide high-quality care. Additionally, an imbalanced patient-to-nurse ratio and the high workload of emergency nurses may contribute to this outcome. Conversely, the mean venipuncture skill scores were higher in pediatric and neonatal wards, likely due to the higher sensitivity of procedures in these wards and the greater expertise of nurses working there.

Conclusion

venipuncture standards are adhered to by 90% of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments: The researchers sincerely thank all the esteemed nurses who participated in this study. Appreciation is also extended to the Honorable Research Deputy of Kashan University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support for this research.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics code IR.KAUMS.NUHEPM.REC.1403.015 was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Health, and Paramedical Sciences at Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing is declared by the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Mousavi SMH (First Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Hosseinian M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (25%); Rezaei M (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%)

Fundings: Nothing is declared by the authors.

Keywords:

References

1. Wherry FF, Schor JB. The SAGE encyclopedia of economics and society. London: Sage Publications; 2015. [Link] [DOI:10.4135/9781452206905]

2. Gholamnejad H, Ghofrani Kelishami F, Manoochehri H, Hoseini M. Efficacy of direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) on practical learning of nursing students in intense care unit. Educ Strateg Med Sci. 2017;10(1):9-14. [Persian] [Link]

3. Babaei M, Jalali R, Jalali A, Rezaei M. The effect of valsalva maneuver on pain intensity and hemodynamic changes during intravenous (IV) cannulation. Iran J Nurs. 2017;30(108):52-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijn.30.108.52]

4. Gorski LA, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, Broadhurst D, Clare S, Kleidon T, et al. Infusion therapy standards of practice, 8th edition. J Infus Nurs. 2021;44(1S Suppl 1):S1-224. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396]

5. Lai NM, Lai NA, O'Riordan E, Chaiyakunapruk N, Taylor JE, Tan K. Skin antisepsis for reducing central venous catheter-related infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD010140. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD010140.pub2]

6. Indarwati F, Mathew S, Munday J, Keogh S. Incidence of peripheral intravenous catheter failure and complications in paediatric patients: Systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103488. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103488]

7. Indarwati F, Munday J, Keogh S. Nurse knowledge and confidence on peripheral intravenous catheter insertion and maintenance in pediatric patients: A multicentre cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;62:10-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.11.007]

8. Whalen M, Maliszewski B, Baptiste DL. Establishing a dedicated difficult vascular access team in the emergency department: A needs assessment. J Infus Nurs. 2017;40(3):149-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000218]

9. Hosseini A, Hossinizadeh Z, Abazari P. Evaluating the competencies of undergraduate nursing students in clinical skills. Iran J Med Educ. 2021;21(1):285-93. [Persian] [Link]

10. Brem BG, Schaffner N, Schlegel CA, Fritschi V, Schnabel KP. The conversion of a peer teaching course in the puncture of peripheral veins for medical students into an interprofessional course. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(2):Doc21. [Link]

11. Lund F, Schultz JH, Maatouk I, Krautter M, Möltner A, Werner A, et al. Effectiveness of IV cannulation skills laboratory training and its transfer into clinical practice: A randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32831. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0032831]

12. Chen YM, Fan XW, Liu MH, Wang J, Yang YQ, Su YF. Risk factors for peripheral venous catheter failure: A prospective cohort study of 5345 patients. J Vasc Access. 2022;23(6):911-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/11297298211015035]

13. Kache S, Patel S, Chen NW, Qu L, Bahl A. Doomed peripheral intravenous catheters: Bad Outcomes are similar for emergency department and inpatient placed catheters: A retrospective medical record review. J Vasc Access. 2022;23(1):50-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1129729820974259]

14. Ahlin C, Klang-Söderkvist B, Johansson E, Björkholm M, Löfmark A. Assessing nursing students' knowledge and skills in performing venepuncture and inserting peripheral venous catheters. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;23:8-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.003]

15. Potter DL, Jefferies DC, Seddon L. Geeky medics OSCE revision guide: Clinical examination. Poole: Geeky Medics; 2023. [Link]

16. Zerati M, Alavi N. Designing and validity evaluation of quality of nursing care scale in intensive care units. J Nurs Meas. 2014;22(3):461-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1891/1061-3749.22.3.461]

17. Arunakumar SPK, Raghunandan BG, Lakshmipathy SR, Ramabhatta S, Rashmi K, Puli R, et al. Improving 'hand-hygiene compliance' among the health care personnel in the special newborn care unit. Indian J Pediatr. 2024;91(1):23-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12098-022-04466-9]

18. Etafa W, Wakuma B, Tsegaye R, Takele T. Nursing students' knowledge on the management of peripheral venous catheters at Wollega University. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0238881. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0238881]

19. Hernon O, McSharry E, Simpkin AJ, MacLaren I, Carr PJ. Evaluating nursing students' venipuncture and peripheral intravenous cannulation knowledge, attitude, and performance: A two-phase evaluation study. J Infus Nurs. 2024;47(2):108-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000539]

20. Jacobs L. Peripheral intravenous catheter insertion competence and confidence in medical/surgical nurses. J Infus Nurs. 2022;45(6):306-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000487]

21. Tomás-Jiménez M, Díaz EF, Sánchez MJF, Pliego AN, Mir-Abellán R. Clinical holding in pediatric venipuncture: Caring by empowering the caregiver. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7403. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18147403]

22. Jones K, Lemaire C, Naugler C. Phlebotomy cycle time related to phlebotomist experience and/or hospital location. Lab Med. 2016;47(1):83-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/labmed/lmv006]

23. Leung A, Li S, Tsang R, Tsao Y, Ma E. Audit of phlebotomy turnaround time in a private hospital setting. Clin Leadersh Manag Rev. 2006;20(3):E3. [Link]

24. Wong CL, Choi KC. Effects of an immersive virtual reality intervention on pain and anxiety among pediatric patients undergoing venipuncture: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e230001. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0001]