Volume 5, Issue 4 (2024)

J Clinic Care Skill 2024, 5(4): 207-213 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/09/9 | Accepted: 2024/12/18 | Published: 2024/12/21

Received: 2024/09/9 | Accepted: 2024/12/18 | Published: 2024/12/21

How to cite this article

Yeganeh M, Ahmadi H, salmani F, Goli S. Role of Nurses in Prevention From Potential Drug Interactions in the Intensive Care Unit. J Clinic Care Skill 2024; 5 (4) :207-213

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-290-en.html

URL: http://jccs.yums.ac.ir/article-1-290-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Nursing & Midwifery Sciences Development Research Center, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1264 Views)

Introduction

In a broad definition, drug interactions refer to reactions that occur when two or more drugs are taken together or when a drug interacts with food, drink, or supplements [1]. Drug interactions are usually predictable in most cases and allow for control in different situations [2]. Consider drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in hospitals where prescribers may be unaware of potential interactions that may occur. Or in certain circumstances, the benefits of the drug are greater than its possible risks. There are more drug interactions [3]. Pharmacology is the science of medicine [4]. Nurses who are well versed in pharmacology. They can detect potentially harmful compounds and flag them for further evaluation by a doctor [5].

In addition to pharmacokinetic modification, which refers to a situation where one drug causes a change in the absorption, distribution, metabolism or even excretion of another drug. There is also the term pharmacodynamics, which refers to the interaction between drugs at the target site or receptor surface that results in altered therapeutic effects or adverse reactions. Interactions into four categories, from most intense to least intense, on your articles. These categories include contraindications, severe cases, moderate cases, and minor cases [6, 7]. Potential drug interactions (PDDIs) are situations in which a drug undergoes changes due to the effect of another drug on it [8].

It is one of the most important drug interactions that can create problems in the future and cause actual drug interactions. In this regard, it can lead to increased mortality or prolonged hospital stays for patients [9, 10]. Łój et al. consider drug interactions to be a serious risk to people's health [11]. Potential drug interactions can lead to abnormalities in metabolic parameters, electrolyte imbalances, and blood count disorders [12]. Which can be dangerous in intensive care units. Based on a 2019 systematic review, it was estimated that approximately 58% of drug interactions occurred in the intensive care unit (ICU) [13]. Fernandes stated in his 2019 article that drug interactions in the intensive care unit increase the possibility of prolonging the QT interval and can lead to acquired long QT syndrome (LQTS) [14]. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) have been responsible for 2.5% to 18% of in-hospital deaths [15, 16]. According to the report of the Ministry of Health in Iran, billions of Tomans are spent annually on medication errors [17].

The process of giving medication to a patient is one of the main and important tasks of a nurse, and doing it correctly can play a significant role in patient safety. Today, there are more than 20,000 types of drugs in the world, all of which, despite their therapeutic effects, can be it can also be harmful. Therefore, nurses should be aware of the correct prescription of medication to identify possible side effects and drug interactions. Given that identifying drug interactions can prevent patient harm and death, as well as dangerous consequences of legal issues between nurses and doctors. However, conducting a comprehensive study on drug interactions can determine the importance of these interactions in general, and nurses can become familiar with these interactions and prevent them [18].

Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of determining potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit and the role of nurses in their prevention.

Information and Methods

The present study was an integrated review of potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit and its agents. In this regard, studies from 2012 to 2024 were reviewed to write an integrated review article based on Russell's model [5, 19].

In this study, the target population included all studies (books, articles, and theses) conducted in adult intensive care units on drug interactions in these units, and access to the entire article or thesis was possible. Our available sources included all studies conducted in the field of drug interactions in adult intensive care units from 2012 to 2024 and were reviewed in this study. The searched databases were CINAHL, Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Wiley, Science Direct, Iran Medex, Scientific Information Database (SID), and Google Scholar.

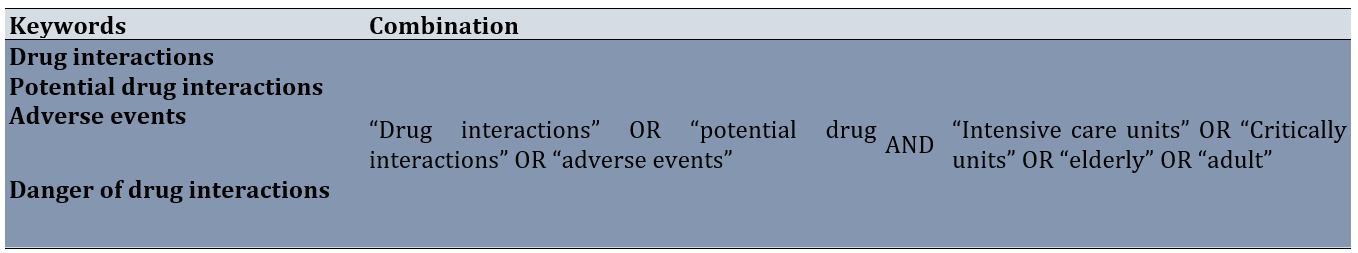

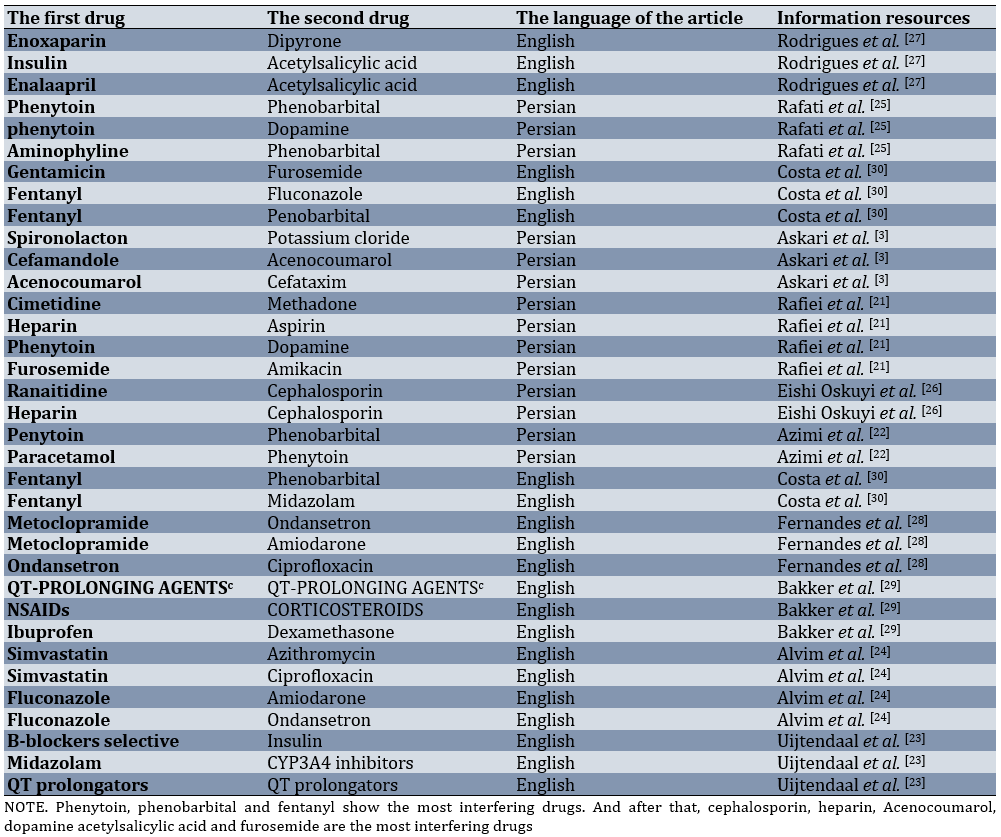

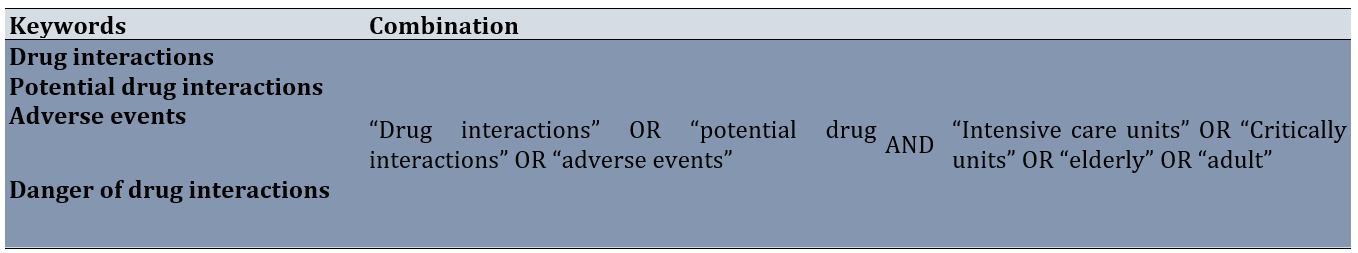

The Persian-English keywords searched were "drug interactions", "potential drug interactions", "adverse events", "intensive care units", "critically units", "risk of drug coexistence", "drug accident", "adult", and "elderly" (Table 1).

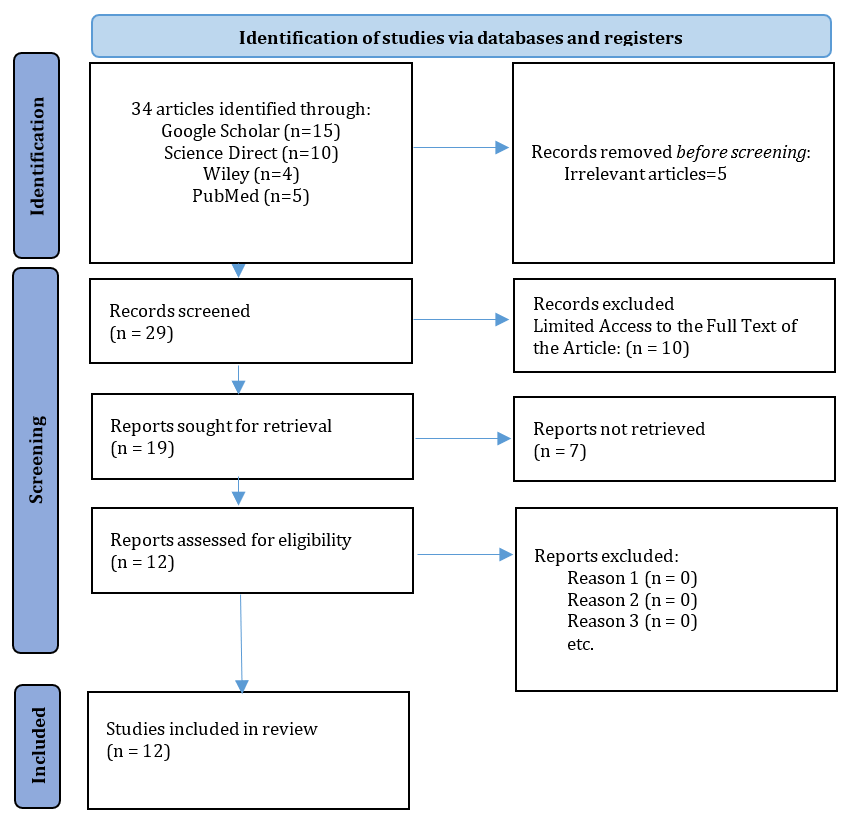

The initial comprehensive search resulted in 34 articles and full abstracts (20 Persian and 14 English). According to the inclusion criteria including articles in Persian or English, access to the full text of the article, and the keyword “Drug Interactions” in the title or abstract, 10 articles (10 articles) were excluded. Subsequently, and after careful review and study of the title, abstract, and full text, a number of other articles were excluded due to different titles and objectives, inappropriate abstracts, and inappropriate article content (12 articles). Finally, 12 articles were included in the study, of which 6 were Persian studies articles and 6 were English articles (Figure 1).

Table 1. Search keywords and how to combine them

Figure 1. Article selection method through PRISMA

All the titles, abstracts and introductions of the existing articles were examined and the most relevant ones were selected for benefit.

At this stage, the quality of the studies was assessed using a critical tool designed by Bowling. This tool includes items designed to examine the methodological structure and presentation of results using a three-point scale of yes, weak, and not reported. At this stage, 7 weak articles were excluded from the study and finally, 12 articles were included in the study [20].

The articles were reviewed separately by two researchers and the results were compared, and if re-review was needed, the validity of the analysis and data was ensured. The process of data extraction and classification was as follows: After the extraction and classification of primary information by the first reviewer, which was done thematically and taking into account various factors affecting the quality of a study, the results were reviewed and controlled by the researcher. The second review and the comments were combined.

After screening the best articles and theses, the results were compared and presented in the form of a final summary of this article.

In the analysis phase, analysis was performed by applying data reduction, data display, data comparison, summarization, and data validation, and the results were presented in the form of separate categories.

Findings

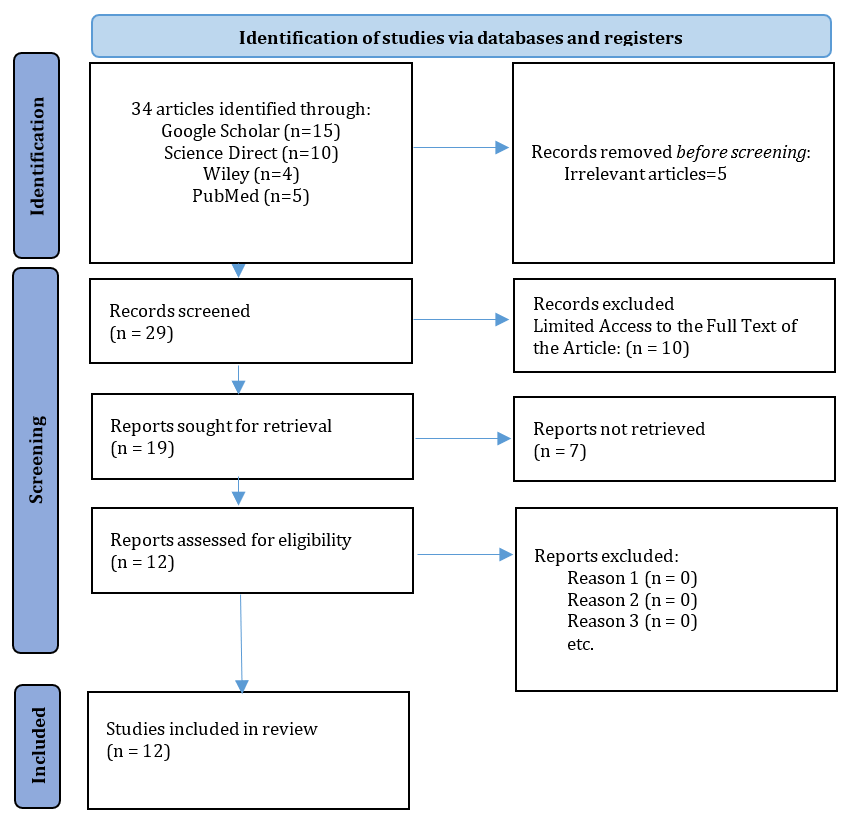

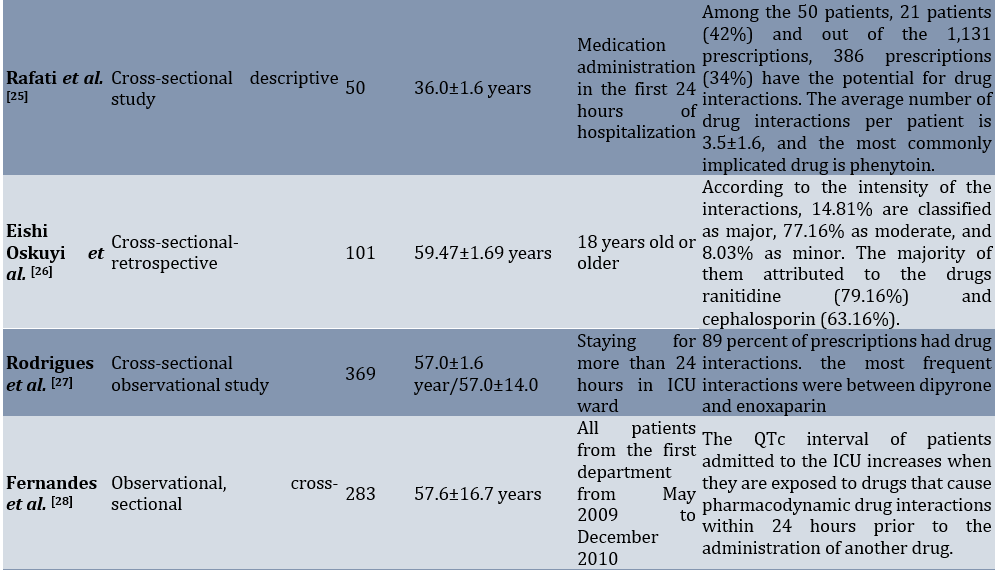

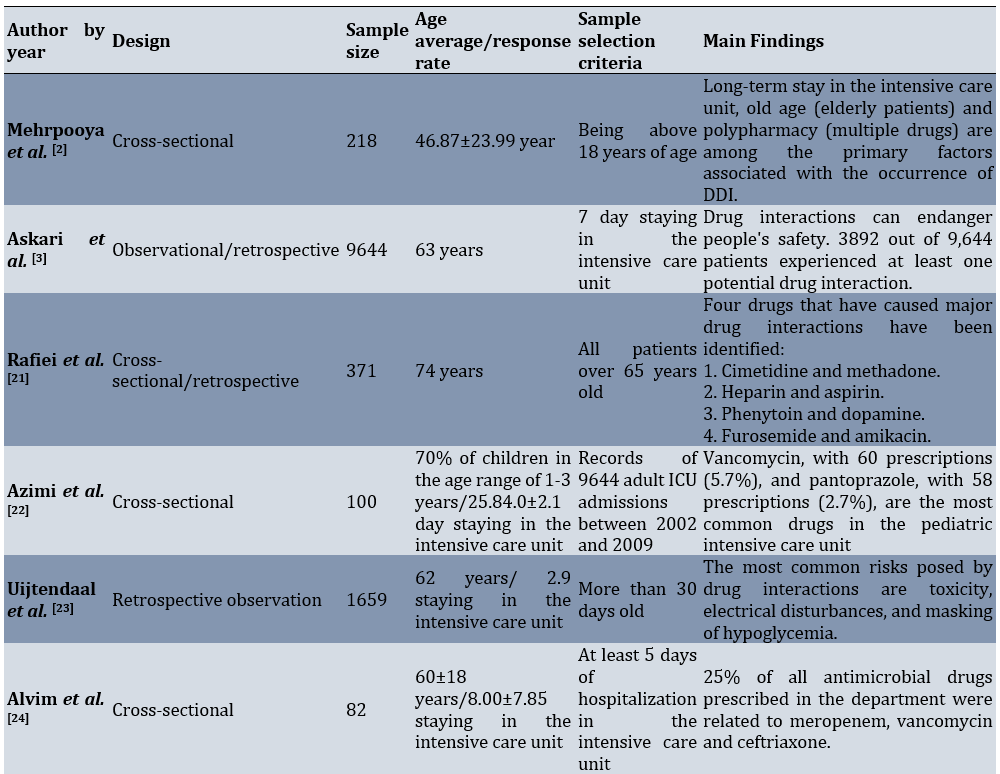

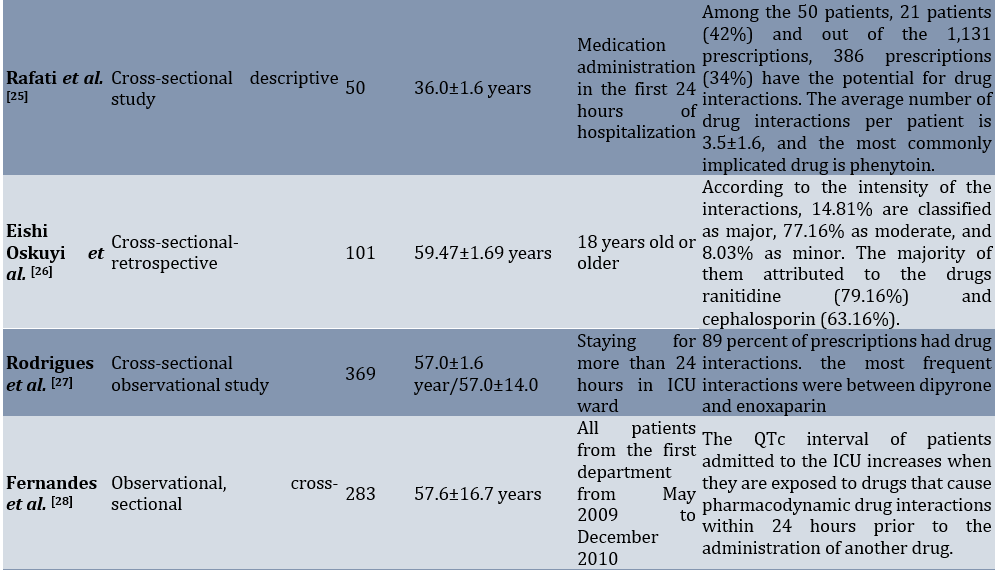

Included studies focused on drug interactions in intensive care units (ICUs) and included various patient populations such as elderly patients, pediatric patients, cancer patients, and neonatal patients. The studies utilized different study designs, including cross-sectional, observational, retrospective, and prospective cohort studies.

The studies identified potential drug-drug interactions in ICU patients, ranging from 70% occurrence in pediatric patients aged 1-3 years to various percentages in different ICU populations. The average ages of the patients ranged from 46.87 years to 74 years, depending on the study.

The studies highlighted the importance of monitoring and managing drug interactions in the ICU setting. They assessed the frequency, nature, prevalence, risk, and management of drug interactions in different patient populations. Some studies also evaluated the risk of QT-interval prolongation associated with drug interactions (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of basic study characteristics

People's age, length of stay, number of drugs prescribed, gestational age, cesarean section and low Apgar score in the first minute are considered as effective factors in increasing drug interactions [2, 27, 28] .

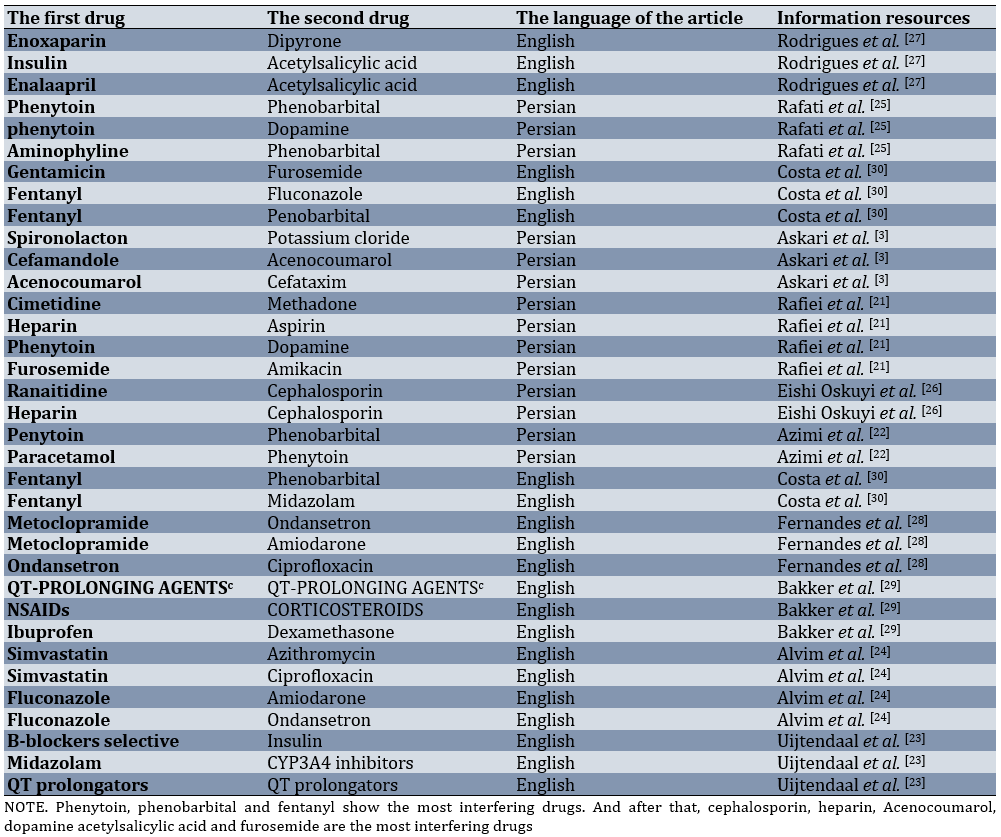

The presence of various common medicinal compounds, the language of the relevant articles and the sources of information was extracted from the articles (Table 3). However, it did not specifically indicate that the drugs phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl have the most interactions.

Table 3. The most interfering drugs in the intensive care unit

Discussion

This integrative review study was conducted to analyze potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit. In the context of understanding the interactions between hospital drugs and food, Ötles & Senturk have found out that the interaction between food and drugs is caused by a physical and chemical relationship, which can be physiological or even pathophysiological [31-33].

El Lassy & Ouda [32] discuss the effect of herbs on drugs and the potential creation of drug interactions [17]. According to the results obtained from Rafiei et al.'s research, it is evident in the intensive care unit that there are reactions between cimetidine and methadone, heparin and aspirin, phenytoin and dopamine, and furosemide and amikacin [21]. Rafati et al., Eishi Oskuyi et al., Costa et al., and Rodrigues et al. introduce phenytoin and phenobarbital, ranitidine and cephalosporin, furosemide-fentanyl-aminophylline-fluconazole, dipyrone and enoxaparin respectively as the most interfering drugs in this section [24, 25]. Nurses carefully review and evaluate any signs or symptoms that may indicate a drug interaction. This awareness can help identify and fix problems in the early stages [34]. Also, nurses are patient supporters and educators. They explain medications to patients, including potential side effects and interactions with other substances, and empower patients to actively participate in their care [35, 36]. Nurses should use computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems with built-in drug interaction alerts to prevent interactions [37].

Through a comprehensive analysis of the full text of the articles, it was determined that gender, length of stay, number of drugs prescribed and age are effective factors in the occurrence of drug interactions in the intensive care unit. In particular, the elderly population is particularly vulnerable to drug interactions due to their weaker immune system compared to other age groups, making them more prone to such incidents. Mehrpooya et al., consider age as an influential factor in the formation of drug interactions in the intensive care unit [2]. During the review of the findings, it was determined that phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl are the drugs with the highest potential for interference. In Persian articles, interactions between phenytoin and dopamine, phenytoin and phenobarbital, and phenobarbital and fentanyl have been mentioned as the most common interactions. English articles describe phenobarbital and fentanyl interactions as the most common drug-drug interactions in the intensive care unit. Among the 31 drugs mentioned with high interference, 14 drugs are related to Farsi language articles and 13 drugs are related to English language articles, without repetition. Four drugs, phenytoin, phenobarbital, furosemide, and dopamine, were frequently mentioned in both languages, highlighting their importance in the intensive care unit [38]. During investigations, it was found that the prevalence of drug interactions is higher among adults in the community, especially those who take multiple medications. Therefore, the use of experienced nurses in intensive care units is recommended [2, 29]. Also, it was found that all the authors discussed the dangerous nature of drug interactions in intensive care units and emphasized the significance of these interactions in comparison to general units [2, 3, 24-26, 31]. In total, the results obtained from internal and external findings reveal that drug interactions can lead to increased risks, which may even result in death in certain situations. In Iran, based on the available reports, a significant amount of money is spent on medication errors every year [39]. This is due to the high accuracy of the work and the reduction in the patient-to-nurse ratio, as well as the creation of clear indicators on the skin and the color of drugs that may interact with each other. Additionally, the use of computer science [3] has contributed to these advancements. By increasing their level of knowledge, nurses significantly contribute to the prevention of drug interactions and ensure the safe administration of drugs to their patients [40, 41].

Therefore, in order to minimize drug interactions and enhance treatment staff accuracy, it is essential to provide comprehensive training courses for the healthcare professionals involved in treatment. One of the limitations of this information was the lack of access to all databases and the lack of access to all articles in full.

Conclusion

Drug interactions have a direct relationship with low Apgar scores, age, long-term stays in the department, and the number of doctors. Phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl are identified as the most interfering in the department.

Acknowledgments: At the end of this article, I would like to sincerely thank all the people who guided us during the writing of this article. Also, the officials of the Islamic Azad University of Nursing, Najaf Abad branch and the IT officials of this university are thanked for providing the necessary and suitable conditions for searching the resources.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Authors' Contribution: Yeganeh M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Ahmadi H (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Salmani F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Goli Sh (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

In a broad definition, drug interactions refer to reactions that occur when two or more drugs are taken together or when a drug interacts with food, drink, or supplements [1]. Drug interactions are usually predictable in most cases and allow for control in different situations [2]. Consider drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in hospitals where prescribers may be unaware of potential interactions that may occur. Or in certain circumstances, the benefits of the drug are greater than its possible risks. There are more drug interactions [3]. Pharmacology is the science of medicine [4]. Nurses who are well versed in pharmacology. They can detect potentially harmful compounds and flag them for further evaluation by a doctor [5].

In addition to pharmacokinetic modification, which refers to a situation where one drug causes a change in the absorption, distribution, metabolism or even excretion of another drug. There is also the term pharmacodynamics, which refers to the interaction between drugs at the target site or receptor surface that results in altered therapeutic effects or adverse reactions. Interactions into four categories, from most intense to least intense, on your articles. These categories include contraindications, severe cases, moderate cases, and minor cases [6, 7]. Potential drug interactions (PDDIs) are situations in which a drug undergoes changes due to the effect of another drug on it [8].

It is one of the most important drug interactions that can create problems in the future and cause actual drug interactions. In this regard, it can lead to increased mortality or prolonged hospital stays for patients [9, 10]. Łój et al. consider drug interactions to be a serious risk to people's health [11]. Potential drug interactions can lead to abnormalities in metabolic parameters, electrolyte imbalances, and blood count disorders [12]. Which can be dangerous in intensive care units. Based on a 2019 systematic review, it was estimated that approximately 58% of drug interactions occurred in the intensive care unit (ICU) [13]. Fernandes stated in his 2019 article that drug interactions in the intensive care unit increase the possibility of prolonging the QT interval and can lead to acquired long QT syndrome (LQTS) [14]. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) have been responsible for 2.5% to 18% of in-hospital deaths [15, 16]. According to the report of the Ministry of Health in Iran, billions of Tomans are spent annually on medication errors [17].

The process of giving medication to a patient is one of the main and important tasks of a nurse, and doing it correctly can play a significant role in patient safety. Today, there are more than 20,000 types of drugs in the world, all of which, despite their therapeutic effects, can be it can also be harmful. Therefore, nurses should be aware of the correct prescription of medication to identify possible side effects and drug interactions. Given that identifying drug interactions can prevent patient harm and death, as well as dangerous consequences of legal issues between nurses and doctors. However, conducting a comprehensive study on drug interactions can determine the importance of these interactions in general, and nurses can become familiar with these interactions and prevent them [18].

Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of determining potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit and the role of nurses in their prevention.

Information and Methods

The present study was an integrated review of potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit and its agents. In this regard, studies from 2012 to 2024 were reviewed to write an integrated review article based on Russell's model [5, 19].

In this study, the target population included all studies (books, articles, and theses) conducted in adult intensive care units on drug interactions in these units, and access to the entire article or thesis was possible. Our available sources included all studies conducted in the field of drug interactions in adult intensive care units from 2012 to 2024 and were reviewed in this study. The searched databases were CINAHL, Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Wiley, Science Direct, Iran Medex, Scientific Information Database (SID), and Google Scholar.

The Persian-English keywords searched were "drug interactions", "potential drug interactions", "adverse events", "intensive care units", "critically units", "risk of drug coexistence", "drug accident", "adult", and "elderly" (Table 1).

The initial comprehensive search resulted in 34 articles and full abstracts (20 Persian and 14 English). According to the inclusion criteria including articles in Persian or English, access to the full text of the article, and the keyword “Drug Interactions” in the title or abstract, 10 articles (10 articles) were excluded. Subsequently, and after careful review and study of the title, abstract, and full text, a number of other articles were excluded due to different titles and objectives, inappropriate abstracts, and inappropriate article content (12 articles). Finally, 12 articles were included in the study, of which 6 were Persian studies articles and 6 were English articles (Figure 1).

Table 1. Search keywords and how to combine them

Figure 1. Article selection method through PRISMA

All the titles, abstracts and introductions of the existing articles were examined and the most relevant ones were selected for benefit.

At this stage, the quality of the studies was assessed using a critical tool designed by Bowling. This tool includes items designed to examine the methodological structure and presentation of results using a three-point scale of yes, weak, and not reported. At this stage, 7 weak articles were excluded from the study and finally, 12 articles were included in the study [20].

The articles were reviewed separately by two researchers and the results were compared, and if re-review was needed, the validity of the analysis and data was ensured. The process of data extraction and classification was as follows: After the extraction and classification of primary information by the first reviewer, which was done thematically and taking into account various factors affecting the quality of a study, the results were reviewed and controlled by the researcher. The second review and the comments were combined.

After screening the best articles and theses, the results were compared and presented in the form of a final summary of this article.

In the analysis phase, analysis was performed by applying data reduction, data display, data comparison, summarization, and data validation, and the results were presented in the form of separate categories.

Findings

Included studies focused on drug interactions in intensive care units (ICUs) and included various patient populations such as elderly patients, pediatric patients, cancer patients, and neonatal patients. The studies utilized different study designs, including cross-sectional, observational, retrospective, and prospective cohort studies.

The studies identified potential drug-drug interactions in ICU patients, ranging from 70% occurrence in pediatric patients aged 1-3 years to various percentages in different ICU populations. The average ages of the patients ranged from 46.87 years to 74 years, depending on the study.

The studies highlighted the importance of monitoring and managing drug interactions in the ICU setting. They assessed the frequency, nature, prevalence, risk, and management of drug interactions in different patient populations. Some studies also evaluated the risk of QT-interval prolongation associated with drug interactions (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of basic study characteristics

People's age, length of stay, number of drugs prescribed, gestational age, cesarean section and low Apgar score in the first minute are considered as effective factors in increasing drug interactions [2, 27, 28] .

The presence of various common medicinal compounds, the language of the relevant articles and the sources of information was extracted from the articles (Table 3). However, it did not specifically indicate that the drugs phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl have the most interactions.

Table 3. The most interfering drugs in the intensive care unit

Discussion

This integrative review study was conducted to analyze potential drug interactions in the intensive care unit. In the context of understanding the interactions between hospital drugs and food, Ötles & Senturk have found out that the interaction between food and drugs is caused by a physical and chemical relationship, which can be physiological or even pathophysiological [31-33].

El Lassy & Ouda [32] discuss the effect of herbs on drugs and the potential creation of drug interactions [17]. According to the results obtained from Rafiei et al.'s research, it is evident in the intensive care unit that there are reactions between cimetidine and methadone, heparin and aspirin, phenytoin and dopamine, and furosemide and amikacin [21]. Rafati et al., Eishi Oskuyi et al., Costa et al., and Rodrigues et al. introduce phenytoin and phenobarbital, ranitidine and cephalosporin, furosemide-fentanyl-aminophylline-fluconazole, dipyrone and enoxaparin respectively as the most interfering drugs in this section [24, 25]. Nurses carefully review and evaluate any signs or symptoms that may indicate a drug interaction. This awareness can help identify and fix problems in the early stages [34]. Also, nurses are patient supporters and educators. They explain medications to patients, including potential side effects and interactions with other substances, and empower patients to actively participate in their care [35, 36]. Nurses should use computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems with built-in drug interaction alerts to prevent interactions [37].

Through a comprehensive analysis of the full text of the articles, it was determined that gender, length of stay, number of drugs prescribed and age are effective factors in the occurrence of drug interactions in the intensive care unit. In particular, the elderly population is particularly vulnerable to drug interactions due to their weaker immune system compared to other age groups, making them more prone to such incidents. Mehrpooya et al., consider age as an influential factor in the formation of drug interactions in the intensive care unit [2]. During the review of the findings, it was determined that phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl are the drugs with the highest potential for interference. In Persian articles, interactions between phenytoin and dopamine, phenytoin and phenobarbital, and phenobarbital and fentanyl have been mentioned as the most common interactions. English articles describe phenobarbital and fentanyl interactions as the most common drug-drug interactions in the intensive care unit. Among the 31 drugs mentioned with high interference, 14 drugs are related to Farsi language articles and 13 drugs are related to English language articles, without repetition. Four drugs, phenytoin, phenobarbital, furosemide, and dopamine, were frequently mentioned in both languages, highlighting their importance in the intensive care unit [38]. During investigations, it was found that the prevalence of drug interactions is higher among adults in the community, especially those who take multiple medications. Therefore, the use of experienced nurses in intensive care units is recommended [2, 29]. Also, it was found that all the authors discussed the dangerous nature of drug interactions in intensive care units and emphasized the significance of these interactions in comparison to general units [2, 3, 24-26, 31]. In total, the results obtained from internal and external findings reveal that drug interactions can lead to increased risks, which may even result in death in certain situations. In Iran, based on the available reports, a significant amount of money is spent on medication errors every year [39]. This is due to the high accuracy of the work and the reduction in the patient-to-nurse ratio, as well as the creation of clear indicators on the skin and the color of drugs that may interact with each other. Additionally, the use of computer science [3] has contributed to these advancements. By increasing their level of knowledge, nurses significantly contribute to the prevention of drug interactions and ensure the safe administration of drugs to their patients [40, 41].

Therefore, in order to minimize drug interactions and enhance treatment staff accuracy, it is essential to provide comprehensive training courses for the healthcare professionals involved in treatment. One of the limitations of this information was the lack of access to all databases and the lack of access to all articles in full.

Conclusion

Drug interactions have a direct relationship with low Apgar scores, age, long-term stays in the department, and the number of doctors. Phenytoin, phenobarbital, and fentanyl are identified as the most interfering in the department.

Acknowledgments: At the end of this article, I would like to sincerely thank all the people who guided us during the writing of this article. Also, the officials of the Islamic Azad University of Nursing, Najaf Abad branch and the IT officials of this university are thanked for providing the necessary and suitable conditions for searching the resources.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Authors' Contribution: Yeganeh M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Ahmadi H (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Salmani F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Goli Sh (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Keywords:

References

1. Malki MA, Pearson ER. Drug-drug-gene interactions and adverse drug reactions. Pharmacogenomics J. 2020;20(3):355-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41397-019-0122-0]

2. Mehrpooya M, Taher A, Golgiri A, Mohammadi Y, Ahmadimoghaddam D. Evaluation of the drug interactions frequency and their related factors in hospitalized patients of the intensive care unit in the Hamadan Besat Hospital. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2021;29(3):171-80. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.30699/ajnmc.29.3.171]

3. Askari M, Eslami S, Louws M, Wierenga PC, Dongelmans DA, Kuiper RA, et al. Frequency and nature of drug‐drug interactions in the intensive care unit. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(4):430-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pds.3415]

4. Buğday MS, Öksüz E. Drug-drug interactions in the risky population: Elderly, urological patients admitted to the intensive care unit. East J Med. 2021;26(2):236-41. [Link] [DOI:10.5505/ejm.2021.04864]

5. Vaismoradi M, Tella S, A Logan P, Khakurel J, Vizcaya-Moreno F. Nurses' adherence to patient safety principles: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2028. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17062028]

6. Rodrigues AT, Stahlschmidt R, Granja S, Falcao AL, Moriel P, Mazzola PG. Clinical relevancy and risks of potential drug-drug interactions in intensive therapy. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;23(4):366-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2014.11.014]

7. Janković SM, Pejčić AV, Milosavljević MN, Opančina VD, Pešić NV, Nedeljković TT, et al. Risk factors for potential drug-drug interactions in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2018;43:1-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.021]

8. Kardas P, Urbański F, Lichwierowicz A, Chudzyńska E, Czech M, Makowska K, et al. The prevalence of selected potential drug-drug interactions of analgesic drugs and possible methods of preventing them: Lessons learned from the analysis of the real-world national database of 38 million citizens of Poland. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:607852. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fphar.2020.607852]

9. Kane-Gill SL, Dasta JF, Buckley MS, Devabhakthuni S, Liu M, Cohen H, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Safe medication use in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):e877-915. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002533]

10. Carollo M, Crisafulli S, Selleri M, Piccoli L, L'Abbate L, Trifirò G. Agreement of different drug-drug interaction checkers for proton pump inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2419851. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.19851]

11. Łój P, Olender A, Ślęzak W, Krzych Ł. Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions in the intensive care unit-Single-centre experience and literature review. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2017;49(4):259-67. [Link]

12. Kovačević M, Vezmar Kovačević S, Radovanović S, Stevanović P, Miljković B. Potential drug-drug interactions associated with clinical and laboratory findings at hospital admission. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(1):150-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11096-019-00951-y]

13. Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, Ehrenstein V, Nicholls SG, Filion KB, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ. 2018;363:k3532. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.k3532]

14. Isbister GK, Page CB. Drug induced QT prolongation: The measurement and assessment of the QT interval in clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(1):48-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bcp.12040]

15. Mouton JP, Mehta U, Parrish AG, Wilson DP, Stewart A, Njuguna CW, et al. Mortality from adverse drug reactions in adult medical inpatients at four hospitals in South Africa: A cross‐sectional survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):818-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bcp.12567]

16. Hansten PD, Tan MS, Horn JR, Gomez-Lumbreras A, Villa-Zapata L, Boyce RD, et al. Colchicine drug interaction errors and misunderstandings: Recommendations for improved evidence-based management. Drug Saf. 2023;46(3):223-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40264-022-01265-1]

17. Nabovati E, Vakili-Arki H, Taherzadeh Z, Hasibian MR, Abu-Hanna A, Eslami S. Drug-drug interactions in inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran: A systematic review of the literature. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2014;22:52. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/2008-2231-22-52]

18. Mosahneh A, Ahmadi B, Akbarisari A, Rahimi Foroshani A. Assessing the causes of medication errors from the nurses' viewpoints of hospitals at Abadan City in 2013. J Hosp. 2016;15(3):41-51. [Persian] [Link]

19. Mohammadi E, Salmani F. The practices and barriers to adult visiting in intensive care units: An integrated review. Nurs Midwifery J. 2020;17(10):780-809. [Persian] [Link]

20. Bowling A. Research methods in health: Investigating health and health services. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. [Link]

21. Rafiei H, Esmaeili Abdar M, Moghadasi J. The prevalence of potential drug interactions among critically ill elderly patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). SALMAND Iran J Ageing. 2012;6(4):14-9. [Persian] [Link]

22. Azimi M, Sanagoo A, Joybari L. The potential drug interactions in pediatric intensive care unit: A case study from Imam Hossein hospital in Isfahan. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;1(4):45-51. [Persian] [Link]

23. Uijtendaal EV, Van Harssel LL, Hugenholtz GW, Kuck EM, Zwart‐van Rijkom JE, Cremer OL, et al. Analysis of potential drug‐drug interactions in medical intensive care unit patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(3):213-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/phar.1395]

24. Alvim MM, Silva LA, Leite IC, Silvério MS. Adverse events caused by potential drug-drug interactions in an intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE TERAPIA INTENSIVA. 2015;27:353-9. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.5935/0103-507X.20150060]

25. Rafati M, Nakhshab M, Irvash M, Rabiee T. Drug interactions in neonatal intensive critical care unit in Bu-Ali Sina Teaching Hospital, Sari, Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2016;25(133):305-9. [Persian] [Link]

26. Eishi Oskuyi A, Valizad Hasanloui MA, Badavi SK, Bahrami Bokani M, Sharifi H. Evaluation of drug-drug interactions in cancer patients admitted to ICU of Imam Khomeiny hospital-Urmia at 2014-2015. Stud Med Sci. 2017;28(3):215-22. [Persian] [Link]

27. Rodrigues AT, Stahlschmidt R, Granja S, Pilger D, Falcão AL, Mazzola PG. Prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions in the intensive care unit of a Brazilian teaching hospital. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2017;53:e16109. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/s2175-97902017000116109]

28. Fernandes FM, Da Silva Paulino AM, Sedda BC, Da Silva EP, Martins RR, Oliveira AG. Assessment of the risk of QT-interval prolongation associated with potential drug-drug interactions in patients admitted to intensive care units. Saudi Pharm J. 2019;27(2):229-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2018.11.003]

29. Bakker T, Abu-Hanna A, Dongelmans DA, Vermeijden WJ, Bosman RJ, De Lange DW, et al. Clinically relevant potential drug-drug interactions in intensive care patients: A large retrospective observational multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2021;62:124-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.11.020]

30. Costa HT, Leopoldino RW, Da Costa TX, Oliveira AG, Martins RR. Drug-drug interactions in neonatal intensive care: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr Neonatol. 2021;62(2):151-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.10.006]

31. Ötles S, Senturk A. Food and drug interactions: A general review. ACTA SCIENTIARUM POLONORUM TECHNOLOGIA ALIMENTARIA. 2014;13(1):89-102. [Link] [DOI:10.17306/J.AFS.2014.1.8]

32. El Lassy RBM, Ouda MM. The effect of food-drug interactions educational program on knowledge and practices of nurses working at the pediatric out-patients' clinics in El-Beheira general hospitals. J Nurs Health Sci. 2019;8(4):34-48. [Link]

33. Hughes JE, Waldron C, Bennett KE, Cahir C. Prevalence of drug-drug interactions in older community-dwelling individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2023;40(2):117-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40266-022-01001-5]

34. Brabcová I, Hajduchová H, Tóthová V, Chloubová I, Červený M, Prokešová R, et al. Reasons for medication administration errors, barriers to reporting them and the number of reported medication administration errors from the perspective of nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;70:103642. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103642]

35. Skidmore-Roth L. Mosby's 2021 nursing drug reference. Maryland Heights: Mosby; 2020. [Link]

36. Manias E, Kusljic S, Wu A. Interventions to reduce medication errors in adult medical and surgical settings: A systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2020;11:2042098620968309. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2042098620968309]

37. Rohde E, Domm E. Nurses' clinical reasoning practices that support safe medication administration: An integrative review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(3-4):e402-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.14077]

38. Neamțu M, Bild V, Ababei DC, Rusu RN, Moșoiu C, Neamțu A. The impact of inflammation and drug interactions on Covid-19 pharmacotherapy. A mini-review. FARMACIA. 2022;70(5):775-84. [Link] [DOI:10.31925/farmacia.2022.5.2]

39. Yeganeh M, Salmani F. Missed nursing care and its associated factors: An integrative review. Med Surg Nurs J. 2023;12(3):e148232. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/msnj-148232]

40. McCuistion LE, DiMaggio KV, Winton MB, Yeager JJ. Pharmacology: A patient-centered nursing process approach. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021. [Link]

41. Lo SY, Reeve E, Page AT, Zaidi ST, Hilmer SN, Etherton-Beer C, et al. Attitudes to drug use in residential aged care facilities: A cross-sectional survey of nurses and care staff. Drugs Aging. 2021;38(8):697-711. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40266-021-00874-2]